Striving for Independence in the World’s Oldest Colony

by James Hammers

Across hundreds of years of colonial history, the people of Puerto Rico have been subjected to foreign governmental control and denied the right of self-determination. While individuals who support American imperialism might point out the capitalistic rituals that have changed work, income, and life in Puerto Rico, those same individuals fail to consider the fact that the people of Puerto Rico should be the ones making these structural choices. Proponents of United States’ colonial rule highlight access to education and consumable goods (i.e. shoes), without considering the possibility that these innovations would have likely become commonplace in a self-ruling Puerto Rico. Despite the ever-present oppression upon the proud people of Puerto Rico and its diaspora, the desire for true independence has also been ever-present. Various periods of Puerto Rican history have seen independence movements fluctuate in intensity; however, this notion does not change the perpetual fight of Puerto Ricans. Independence movements have been visible across all areas of Puerto Rico’s diaspora including but not limited to mainland Puerto Rico and New York City.

Photography, a means of recording, creating, capturing, stating, exclaiming, and lying has played a dynamic role in Puerto Rican independence. Cameras became portable and more accessible while Puerto Rico became colonized by the United States. This precise timing saw photography evolve with the United States controlled Puerto Rico.

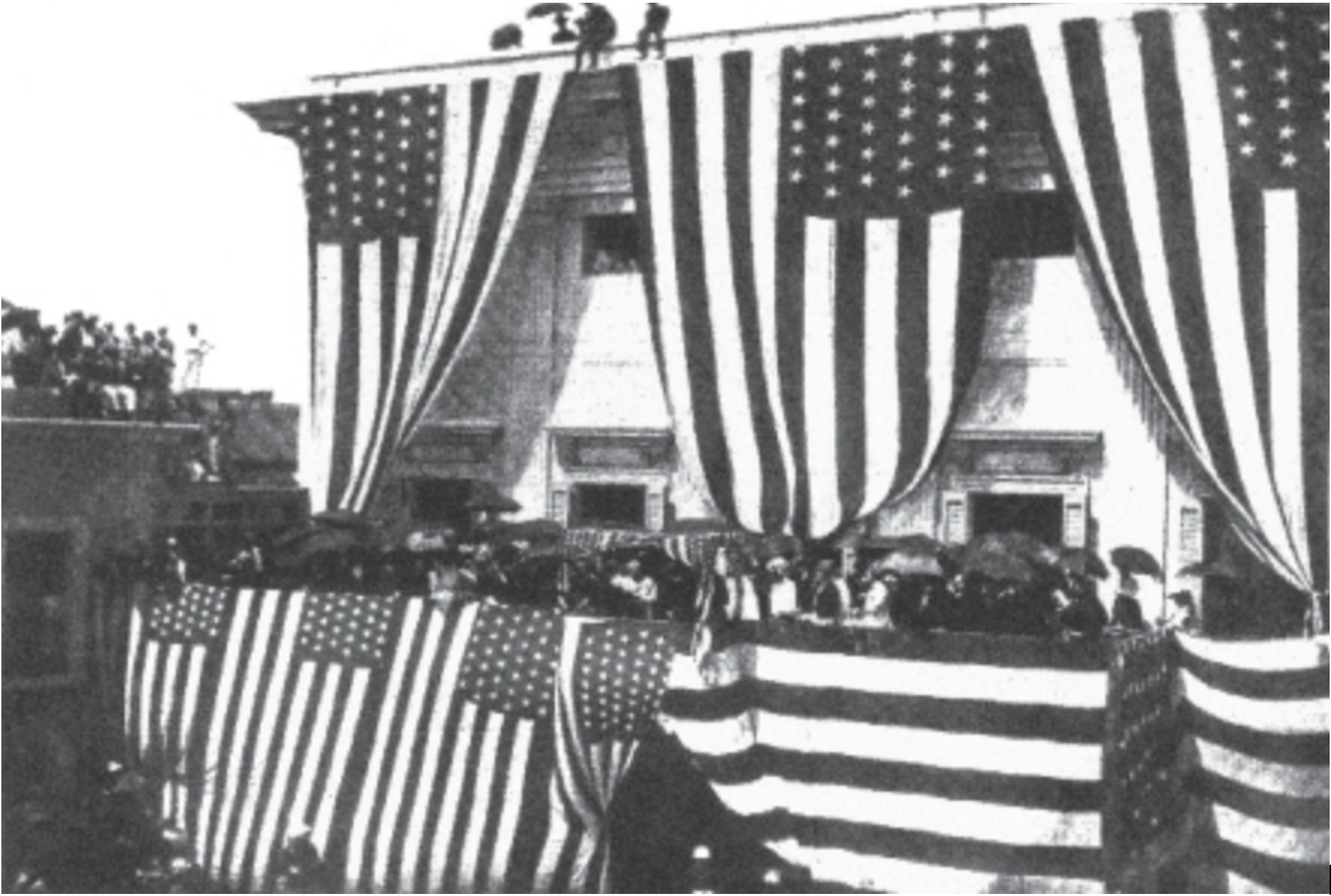

The following sequence characterizes the evolution of United States controlled Puerto Rico and the intensity of the desire for Puerto Rican independence. Initial images depict the placement of the first United States appointed Puerto Rican governor, while later images showcase the political unrest that inevitably arose through decades of colonization and subversion to foreign control. At the same time, because of the optimal timing, camera work (photography) itself evolves with the photographic sequence. The first image, low quality and lacking meaningful detail aside from several American flags, speaks to how Puerto Ricans were made unimportant and subservient to the United States and their appointed governor. This initial image, dreamlike in its fuzziness, serves as a distorted omen for the carnage that will follow from the American occupation of the Caribbean nation. Meanwhile, cameras change from the early limited quality to horrifying, vivid candid street imagery, police force spy footage, and assembly photos with dozens of faces in high quality. Cameras serve as tools for visibility, coercion, and a reminder of terror, and this remains true today, especially with social platforms bringing issues to the eyes of consumers aside from what media conglomerates wish to show them.

Our first image, “Inauguración del gobernador Charles Herbert Allen”[1] taken in 1900, from Guerra Contra Todos los Puertorriqueños: Revolución y Terror en la Colonia Americana by Nelson A Denis pictures Charles Herbert Allen’s inaugural ceremony. Critically, Allen was not elected by the Puerto Rican people. President William McKinley appointed him shortly after the establishment of civilian government in Puerto Rico. The image is dark and ominous showcasing a balcony full of individuals, likely including Allen, holding umbrellas to protect themselves from Puerto Rico’s tropical showers. Beyond the individuals on the balcony, there are a collection of individuals across rooftops, seeking to witness the events of the inauguration ceremony. The sheer number of individuals watching the ceremony steps outside of the linear, colonial concept of time. They know they should be watching this event not only because of the event itself, but it is as if they know how dramatically it will alter the existence of Puerto Rico as a nation of people.

A defining feature of the Inauguración del gobernador image is repetition or more fittingly patterning. Individuals holding their umbrellas across the image prepare to weather turmoil that will ensue throughout United States occupation of Puerto Rico. Another image blasted across the photographic canvas are the (at minimum) 9 American flags. The American flags feel strongly imposing, the same imposition that the Puerto Rican people experienced as subject to American control while being denied self-determination. What I notice specifically from the various American flags is the linearity with its design. The straight vertical and horizontal lines point to the linearity with which the American colonial model approaches various aspects of life including time. Another linear model that the United States would impose on Puerto Ricans is labor. In efforts to increase production and profit as much as possible, traditional labor, unbounded by long work weeks was switching in for factory-based monotonous labor, and perhaps the linearity of the American flags presented foreshadows these changes.

Curiously, a “Puerto Rican” inauguration event lacks an important image: the five striped, red, white and blue Puerto Rican flag. This omission is precisely why I chose to study the Puerto Rican flag and the independence movement for this final exhibition. A sign of strength denied a ticket to a defining moment in its history speaks to its power and its meaning to Puerto Rico as an independent nation.

The camera serves as a historical recording device, tracking the beginning of a storied history in control and struggle for independence.

Image two, “Víctimas de la Masacre de Ponce, asesinados un Domingo de Ramos”[1] photographed by Carlos Torres Morales on March 21st, 1937, taken from Guerra Contra Todos los Puertorriqueños: Revolución y Terror en la Colonia Americana showcases a truly horrific image of dead citizens, executed by Police after a peaceful permitted march. The photo showcases an active frame, causing devastated eyes to dart back and forth across the image to question what exactly they might be looking at. Four bodies of young men lay on the street following execution.

For background context, following an initial granting of permission to participate in a peaceful demonstration, an appointed U.S. governor, fulfilling the same role as the subject matter of the previous photograph revoked the very same permissions. This led to the police opening fire on unarmed demonstrators and even bystanders, killing 19 individuals and injuring hundreds. Critically, this protest was peaceful, and the police used excessive and unjustifiable force. The participants of this protest were members of an explicitly pro-independence group for Puerto Rico. Although not confirmable, what lies next to the young, executed man dressed in bright clothes is what appears to be a Puerto Rican flag. Whether it is a flag or merely a metaphorical reminder, lying lifeless next to a Puerto Rican flag because of the imperial orders speaks to the oppression with which independence desires were unheard, smothered, and denied. Not only did participating in an event by the independence party lead to being met with extreme resistance, but it was met with mortality.

In simplicity for an image that is anything but simple, this image showcases the truth and horror that colonial oppression can be. Where pictures of malls decorated with American businesses conjure up fond memories for many individuals pro-independence and pro-American individuals alike, there are counter images that showcase the horrors of colonial oppression and what extreme control from colonial oppression can lead to. It almost becomes intuitive to think of this image as a warning, but it is not a warning, the damage has already been done. The previous image, where the United States colonial grasp swiftly reaches over Puerto Rican government was the warning, and the following images depict the tensions that and breaches of human rights that follow.

Returning to image and thematic analysis, this image forms a direct relationship with the previous photo in the image sequence. The warning that the former photo provided came to fruition with the lives of these young Puerto Rican men. The parallel lines from the American flags in image 1 now exist as parallel bodies lying on the ground. The governmental position in image 1 now orders the death of the people who want to be freed from colonial rule for the first time in over 500 years.

Image 3 from El Gobierno Te Odia [1]by Christopher Gregory-Rivera showcases spy shots from police attempting to photograph the Independence movement in Puerto Rico during the 1970s. The role of the camera in this photo is to exploit the protestors in this photo, find who they are and punish them for their involvement in the independence movement. The protestors intelligently cover their faces and one of the individuals sports a Puerto Rican flag on their face, proudly displaying a beacon of hope on the subject that the police desperately attempt to photograph.

The image itself feels like a spy shot. The image is decorated with graininess and lacks a bit of clarity, perhaps speaking to the lack of expertise by the police in photography. What’s more, this graininess characterizes the photograph as if it’s been exposed to elements. It seems as if (although not the case in reality) that the film has been chipped away by wind and sand.

None of the subjects are focused on the image at first glance, aside from a few individuals donning sunglasses that may or may not be looking directly at the camera. This unknown quality or where many of the subjects are looking speaks to mystery and anonymity. In truth, the Puerto Rican Independence movement is not and has not been about individualism, it is the collective of individuals who are Puerto Rican who desire to allow Puerto Rico to govern itself.

Furthermore, another defining detail of this pro-independence spy image is the fact that all the individuals are wearing clothing that looks like it’s from vastly different periods of time. It’s almost as if time itself ceases to exist in this image because linear time is not a defining characteristic of Puerto Rican Independence. Individuals at the bottom of the screen where baseball caps and, hoods, and aviator sunglasses, styles that range from the 1950s to 1980s. Above them, other individuals wear similar clothing but two stand out individuals wear an old hat that appears to be from the 1940s at the left, in the brightest shirt, and the man at the right wears a collared shirt that places him anywhere from the 20s to 60s, as far as attire goes. Finally, a man in the center that immediately draws the attention of the viewer wears modern sunglasses and a flat-bill baseball cap, style that points to the 2010s. The various eras of attire within the image truly water the effects of time and show that Puerto Rican independence is not a fleeting cause, but an ever-present desire.

The fourth and final image from Guerra Contra Todos los Puertorriqueños: Revolución y Terror en la Colonia Americana captioned “Asamblea estudiantil en la Universidad de Puerto Rico; bajo la Ley de la mordaza número 53, todo el mundo en esta asamblea corrió el riesgo de ser arrestado y encarcelado por diez años por motivo de la presencia de la bandera puertorriqueña”[1] which translates to “Student assembly at the University of Puerto Rico; under the Gag Law, Law 53, everyone at this assembly ran the risk of being arrested and imprisoned for ten years due to the presence of the Puerto Rican flag” shows a full circle moment in the emergence of the Puerto Rican Flag.

In our given sequence, we see the flag emerge over time. From complete omission to being rolled up next to an executed protestor, to donned on the face of another, to the backdrop for dozens of individuals supporting a cause they would risk being arrested for, the flag experiences a range of exposures. Speaking of exposures, the cameras change dynamically across the movement, as evidenced by lackluster exposure and clarity initially to dozens of crystal-clear faces in this final image, yet that hunger and willingness to die for independence doesn’t evolve at its core. The sheer number of individuals in this image speak to that ever presence and wide-spread commitment especially considering the potential for arrests.

I find it considerably fascinating how powerfully a role the flag finds itself in. Even in the first image where it is not visible, I am reminded of it. As much as the independence movement for Puerto Ricans waters time and remains a truth in Puerto Rican culture and political strive, the flag (especially the light blue Puerto Rican flag) water visuality and serve as both a visual and conceptual reminder of many Puerto Ricans desire for Puerto Rico to govern itself.

Works Cited:

[1] Nelson A. Denis, Guerra Contra Todos los Puertorriqueños: Revolución y Terror en la Colonia Americana (New York: Nation Books, 2015)

[2] Carlos Torres Morales, “Víctimas de la Masacre de Ponce, asesinados un Domingo de Ramos,” photograph, March 21, 1937, in Nelson A. Denis, Guerra Contra Todos los Puertorriqueños: Revolución y Terror en la Colonia Americana (New York: Nation Books, 2015)

[3] Christopher Gregory-Rivera, El Gobierno Te Odia (New York: Rizzoli, 2021)

[4] Asamblea estudiantil en la Universidad de Puerto Rico,” photograph, Los Papeles de Ruth Reynolds, Archivos de la Diáspora Puertorriqueña, Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Hunter College, CUNY

Photographic References

Asamblea estudiantil en la Universidad de Puerto Rico.” Photograph. Los Papeles de Ruth

Reynolds, Archivos de la Diáspora Puertorriqueña, Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños,

Hunter College, CUNY

Denis, Nelson A. Guerra Contra Todos los Puertorriqueños: Revolución y Terror en la Colonia

Americana. New York: Nation Books, 2015

Gregory-Rivera, Christopher. El Gobierno Te Odia. New York: Rizzoli, 2021

Torres Morales, Carlos. “Víctimas de la Masacre de Ponce, asesinados un Domingo de

Ramos.” Photograph, March 21, 1937. In Guerra Contra Todos los Puertorriqueños: Revolución y Terror en la Colonia Americana, by Nelson A. Denis. New York: Nation Books, 2015