By Jalilah Lamptey

The first documentary photography of Puerto Rico held a perverted fascination with the architecture that could be found on the island. The “typical” and “native” was provided as an example of the current desperate state of Puerto Rican society, and a justification for the exertion of colonial and imperial power on the island. In the 20th century, documentary photographers once again proffered images as an example of the economic advancements made in Puerto Rico. According to their photography, Puerto Rico was now a highly developed, Americanized colony that fit in with the rest of the mainland perfectly. Whenever a hurricane hits, images of the destruction of Puerto Rico flood the news, exposing and in many cases exploiting the suffering of the island. While, on one hand, architectural photography is deeply important to the creation of an archive and can serve as a seemingly neutral time capsule through which we can understand how the past looked, architectural photography is highly curated and skewed. Formal decisions are always made, and these decisions impact how we understand the photographs and their content, often inserting or implying a biased account of the subject matter. Through the exploration of archives of three sets of architectural photographs in Puerto Rico, this project will explore how these photos cannot be disentangled from wider stories of class, environment, and colonial networks.

In 1846, the Cathedral of Saint Philip the Apostle was constructed in the Puerto Rican city of Arecibo. At this time, Puerto Rico was subject to colonial Spanish power, which meant the introduction of Christianity in the form of Roman Catholicism. The first photo that this project will explore is of the Cathedral. It is a photo of the base of a light blue pilaster in front of a facade with light beige and off-white portions. To the left, a ramp leading into a small portion of a doorway can be seen, leading into a dark room. Below the facade, there is sidewalk covered in gum with a few weeds growing out of it. The lighting of the photo is extremely bright, and one could guess that it had been taken at midday. It is extremely close up, with a passive frame. There are no physical people captured in this image. Although the photo seems to provide limited information, close analysis reveals complex dynamics surrounding colonialism, the environment, and care. There are no people in this photo, but their presence can be felt. The paint on the pilaster, wall, and foundation is neat and clean. It is not chipping or peeling, which are both inevitable results of time spent in conditions with salty air, especially apparent in the coastal town of Arecibo. Someone has been maintaining this space. In contrast, the large amounts of gum on the concrete sidewalk also signify human presence. One could imagine countless people walking past this building and spitting out the gum they were chewing. The photo, however, provides very little in terms of historical context. This is where its description comes in:

(1)

Close-up view of the details of the Cathedral of Saint Philip the Apostle in the coastal city of Arecibo. The building is made of masonry with a concrete roof; its design is inspired by Renaissance and Neoclassic architecture. The facade has a flat pilaster over a base; the entrance opening is visible to the left far end. The construction of the Cathedral of Saint Philip the Apostle dates back to 1616; nonetheless, in 1846, the building was officially built, according to the design observed in the photo. It is the second-largest church built on the island under Spanish rule, and it was not until 1960 that it was officially designated the Cathedral of the Diocese of Arecibo. (2)

From this description, we learn what building is in the photo, about the European influence on its architecture, and its history and significance.

A contradiction arises between the form of the photo and its description. Although the formal decisions of the photo, particularly its close angle, obfuscate the identity of the building and the style it is in, this description provides almost too much information about the context of the photo. We cannot see the roof of the building, or even that it is a church at all. We cannot know where it is located, or when construction for it began. Due to this information gap, this photo could be viewed as a re-frame. If we view this photo as a reframe, what has been cropped out of the image?

I wanted to create a material exploration that envisioned what the original photo had looked like. Using the other photos in the archive that are also of the Cathedral of Saint Philip the Apostle, I decided to create a collage and place the photo back in its original context. Through this material exploration, it was clear that the photo I chose to primarily focus on had misled me. The building is in fact in worse condition than I had thought, and this particular spot is one of the best maintained. The photo did not fit in well with any of the other ones of the same building, showing not only the biases of architectural photography but also the shortcomings of two dimensional photography in capturing the realities of a building in numerous dimensions.

Moving beyond this first exploration, I next tried to put the photo in contexts that it did not belong to, placing it on top of photos from Princeton University Art Museum’s Minor White Collection. It fit better with Minor White’s photos due to the similarly form-focused, straight-on, artistic, photographic style. Although these buildings are unrelated, the photos very well could be given the limited visual context provided. The camera simultaneously obscures context and creates a relation among the photos (that does not exist) through formal decisions like cropping, framing, and angle. The deliberate and manufactured obscurity and ambiguity through intentional formal decisions allows the photo to move through time and space more freely, interacting with photos it otherwise never could. Furthermore, intentional cropping allows for a sort of reversal of the eventual environmental deterioration of the building. In the one small photo we have, the environment has not impacted the Cathedral. Instead, it appears pristine and untouched by environmental conditions.

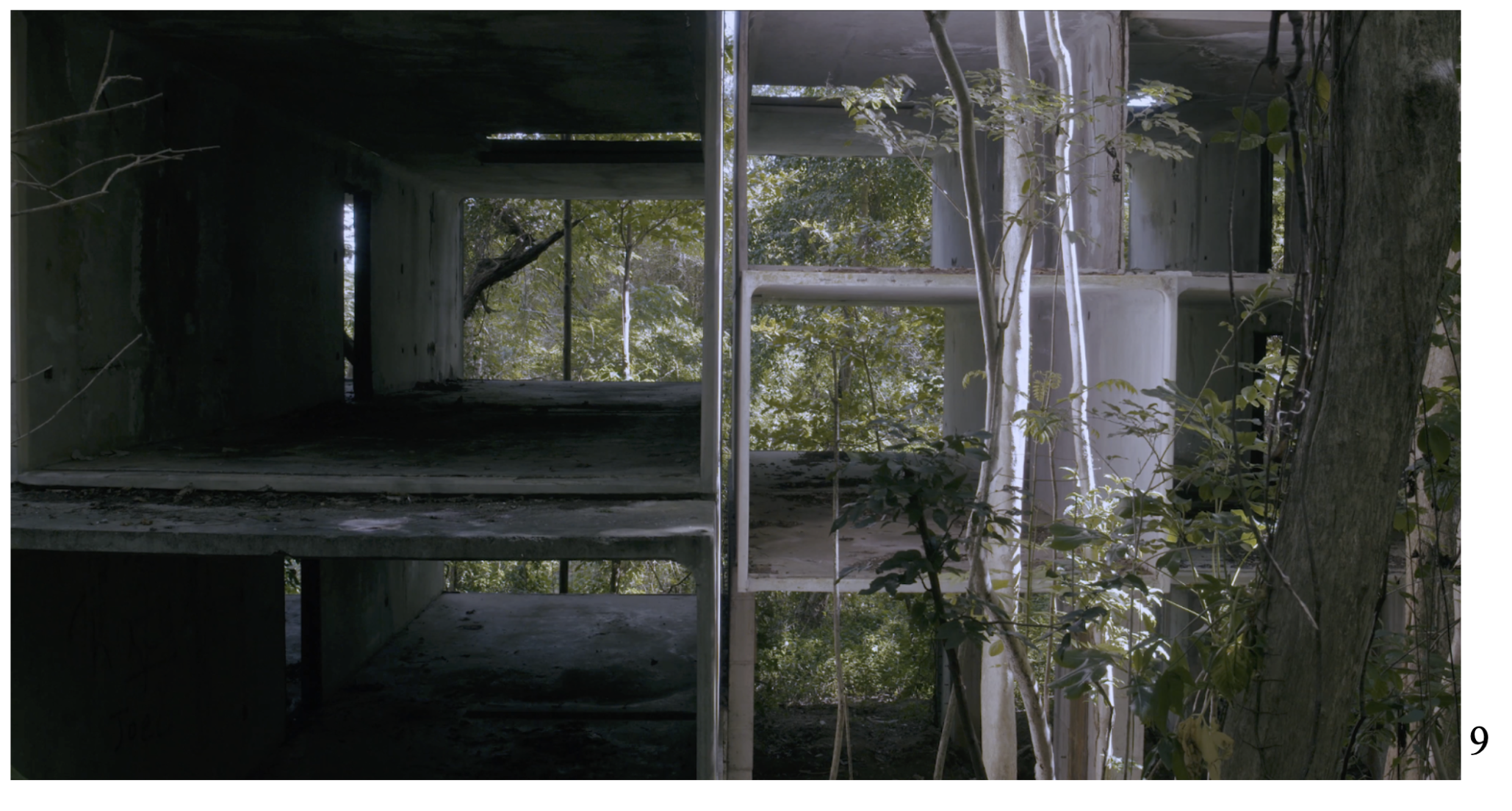

An opposite phenomenon, arguably, can be seen in images of architect Moshe Safdie’s 1968 Habitat Puerto Rico. Part of the postwar boom in constructivist, experimental housing, it was an adaptation of his previous work to a uniquely American condition, the Title 236 moderate-income housing program, which ensured middle and low class housing for the residents of Puerto Rico and the rest of America. It consisted of “800 prefabricated and prefinished concrete housing units, 40 square meters each, were to be delivered by truck or barge to the site.” (3) They were entirely prefabricated in factories with everything they needed, including appliances, but were adaptable to a variety of different lifestyles and layouts onsite. Their design was maximized for efficiency. A wider community was planned around them, consisting of “hill shops, cafes, community rooms and offices, 14-story high-rise towers, and an outdoor amphitheater…. Substantial areas of the hill are left untouched to preserve the natural vegetation.”(4) Despite ambitious planning, construction stopped after 30 housing units were installed due to a loss of financial support from the government.

Habitat Puerto Rico, model showing terraces and view from walkway system, 1968.

(Image credit: Courtesy of Safdie Architects)

The attempted construction of and failed completion of experimental housing projects like Habitat Puerto Rico was not an uncommon global phenomenon at that time. The presence of these architectural plans–today, architectural ruins–serves as evidence of the participation of Puerto Rico in these trends. It places Puerto Rico in a very specific timeline that stretched from the island to the mainland United States to France and even to the Soviet Union. It also demonstrates the influence of international architects on Puerto Rican geography. Although not Puerto Rican, Safdie was able to undertake this massive housing project on the island.

Since Habitat Puerto Rico never came to fruition, all of the images we have of it in a nonabandoned state (above images) are either of architectural models or of the process of construction. The photos of the architectural models are highly manufactured. The camera is zoomed in and positioned in a way that allows it to distort falsehood (the model) into a sort of plausible possibility. It is obvious that the images are not of actual people or architecture, but the photos are supposed to encourage belief in the project and sell a convincing future. They are advertisements. Even the photos of the construction serve this purpose; they do not show the troubles of construction but the successes. They express that progress is happening, and that ideas are becoming reality. There is no nature in these photos. Idealism has succeeded.

Contemporary imagery of the abandoned buildings of Habitat serves an entirely different purpose, and the material exploration of sequencing can help to reveal this change.

A film created by the artist David Harrt consists of long shots of the buildings paired with layered field recordings as “traffic fades into the distance and the noise of the insects and birds comes to the fore.” Nature is present in this film, and even prioritized. The camera becomes investigative. It is used to remember the past and to prevent the act of forgetting. The environment is not something to be neatly incorporated into plans, but is emphasized in order to indicate how much time has passed since construction started on Habitat Puerto Rico. This echoes conversations about the legacies of colonialism and international influence today. The camera, with the help of nature, creates temporal distance, reminding observers of how long international interference has been happening in Puerto Rico, the constant failures of the government to attend to Puerto Rican needs, and how much post-war optimism has diminished since the late mid twentieth century.

In the case of the first two sets of photos (the Cathedral and Habitat Puerto Rico), framing and visual choices in the photography directly grapple with the environmental impacts of the coastal, tropical Puerto Rican climate. In the case of the final photo I will explore, Orocovis #27, the formal decisions and visual choices are unrelated to the environment. Instead of being immediately captured in the moment the shutter is released, environmental impact becomes visible in the archive itself. Although the moment of photographing is over and the photo has been taken, the environment changes the photograph after the fact. The photo depicts a two storey building with siding and a brown door. Two people sit on the balcony. One reads, standing. The other looks up and is sitting, leaning against a porch support beam. A woman walks by outside the house. The photo is taken with a diagonal angle, presumably from across the street from the building. Next to the main house stands another similar house. Although the definite date of the photo is unknown, the outfits of the three women pictured, along with the building’s jalousie windows, means the photo most likely dates to the mid-late twentieth century. This was the time of important economic changes for Puerto Rico linked to Operation Bootstrap, the leadership of Luis Muñoz Marín, and the documentary photography of photographers like Jack Delano. This may be an image of a new housing development.

Unlike the other images explored in this project so far, this is actually a photo of a polaroid. It is a piece of physical media, rather than a digital scan or photo. This affords new opportunities for understanding environmental impact, since this physical object would have lived in personal or state collections for most of its life. In the middle of the top of the polaroid, there are five brown spots. Another is located in the top left of the polaroid. There is also dust and hair on the surface of the photo.

The brown spots on the image have a sort of tactile quality to them. It is unclear what they are. Mold? Dirt? Food residue? A scratch? An attempt to recreate this photo and its brown spots did not answer this question, as I was not able to replicate the brown spots exactly. Clearly, they are the result of specific environmental conditions that are not easily replicated. In this case, the act of photography was unimportant to this environmental impact beyond the fact that it created a material object: the polaroid. It was the storage of the polaroid, and the way it changed over time, that led to a commentary on the challenges the climate of Puerto Rico poses to the creation of an archive and preservation of material in its initial form.

Each of the three sets of photos explored in this essay reflect a different relationship with the environment. The first shows the relationship between human presence and maintenance in the face of environmental degradation over time. The second shows the decaying legacy of international housing trends in Puerto Rico. The third contrasts the economic boom in Puerto Rico with the contemporary struggles tropical archives face. Despite their differences, all of these images exemplify the relationship between time and the environment. The environment has and will continue to change, regardless of human presence. While it follows predictable patterns on regular time scales, it also has random instances of unpredictability. The human relationship with the environment, as exemplified in these photos, is a battle with time, an attempt to predict, and a hope to overcome. In this sense, architectural photography is not and cannot be neutral. It also cannot be neutral because of the formal decisions made by photographers when an image is taken. These decisions, in a way, form another aspect of the environment, an environment that is shaped by class, development, and colonial networks.

Works Cited:

(1) “Cathedral of Saint Philip the Apostle - Arecibo - 2013 00006,” 2013, Colección Pueblos, PRAHA Digital Archive, https://prahadigital.org/s/flmm_en/item?uid=f1e1c7d8-292a-11ef-a756-0242ac190002.

Accessed December 9, 2025.

(2) ibid

(3) Habitat Puerto Rico, 2015, The Moshe Safdie Archive, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill Library, https://cac.mcgill.ca/moshesafdie/fullrecord.php?ID=10820&d=1. Accessed December 9, 2025.

(4) ibid

(5) Habitat Puerto Rico, model showing terraces and view from walkway system, 1968.

(Image credit: Courtesy of Safdie Architects)

(6) Model detail by Safdie Architects, The Moshe Safdie Archive, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill Library, https://cac.mcgill.ca/moshesafdie/fullrecord.php?ID=10820&d=1. Accessed December 9, 2025.

(7) Habitat Puerto Rico. Prefabricated module, 1968. Courtesy Safdie Architects.

(8) David Hartt, Modern Ruins: “An Artist’s Take on Moshe Safdie’s Puerto Rican Forest Habitat,” PIN–UP 22, Spring Summer 2017. PIN-UP Magazine

(9) David Hartt. Still from In the forest, 2017. 4K Digital Video File, colour, sound; 20 min. Courtesy of Corbett vs Dempsey and commissioned by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

(10) https://thespaces.com/moshe-safdie-habitat-puerto-rico-david-hartt-in-the-forest/