Differentiable and Continuous

Sometimes, the pursuit of artistry and insightfulness leads to a sort of tunnel vision, where the preconceived notions of what a final product should look like dominates the process of creation. Indeed, too often it happens that we spend so much time trying to harrow into one specific thing, that we miss the art that unfolds right in front of us in the meantime. This is true both of the way I initially approached this project, and of the way I approached its source materials. Perhaps appropriately, this project circles back towards the beginning of the semester, and focuses on Jack Delano’s works in Puerto Rico Mío, a collection of photographs carefully curated across his years living and working in Puerto Rico, with emphasis on his initial work in the 40s being put into conversation with a retour of the entire nation in the late 70s and 80s.

Initially, I had not intended to grapple with Delano’s material at all here, having regarded it earlier in the semester as an interesting reinforcement of an economically booming United States colonel-esque views on Puerto Rico, but not much else. It was only in taking the time to look past these notions that I learned I had mistaken intentionality for ignorance, and left myself entirely unaware of the progression of his works, both photographic and not, in Puerto Rico. To say that Puerto Rico Mío achieves any one thing in particular would be a terrible mistake, as it is in many ways a reflection of Puerto Rico itself. That is, the Puerto Rican culture, especially in the time period the book covers, has evolved rapidly, and yet in many ways holds close to its cultural roots. More than anything else, Delano’s work is an indicator of the fact that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

To discuss the context of each photograph in Puerto Rico Mío would be to review Puerto Rico as a whole between the 40s and 80s, for the book is a fairly comprehensive documentation of many factors of the nation’s culture. To best understand his early work in particular, it is more intuitive to understand how Delano’s role evolved throughout the 40s. Delano’s career as a photographer launched largely with his employment with the Farm Security Administration, which locally within the United States had been established as a New Deal program that documented, among other things, working conditions across the country. Prior to being assigned to Puerto Rico, Delano worked alongside sociologist Arthur Raper in Georgia. Raper had been working on a book titled Tenants of the Almighty, in which he documented the difference socioeconomic conditions between white and African American residents. In particular, Delano’s own contributions documented the state of educational access in the state. Through this work, it is clear that Delano’s work takes two forms. One is, as Raper himself noted, that Delano liked to photograph about issues which had the potential to be addressed and resolved with sufficient attention to the matter, and in this sense Delano very consciously treated photography as a force of change. On the other hand, through working with Raper, Delano’s reflect a notion of humanity through visibility in a community. That is, the way for a broader society to see a group of people, and not merely gloss over them, is to make them visible; when such visibility is tied to the workings of the institution of the FSA’s work, visibility thus translates into the proper functionality of an institution, rather than coming from the people themselves.

This is largely why Delano’s early works, and indeed my own initial reflections on him, come under such criticism. Seen right is one of Delano’s 1941 photographs, meaning that it was one of the photographs taken during his first time on the island. Initially, Delano was only to stay for a few days on his way to the Virgin Islands, but his initial stay ended up a several-months long project after US entry into World War II delayed his exit. Many of Delano’s earlier works, and indeed those first photographs in Puerto Rico, mimic this style, in which the emphasis is very much on the fiscal poverty of the situation. As Puerto Rican writer and Guggenheim Fellow noted in his review of Puerto Rico Mío “in 1941, he was an americano employed as a photographer by a colonial agency, the FSA, which collected our sorrow, passivity, and hopelessness with the passion of an antiquarian who sees his stock grow” (Rodríguez Juliá in del Pilar Blanco). The framing is such that the subjects dominate the frame. Whilst they are not looking at the camera (as is often the case in Delano’s early works), they are very much aware of his presence, and thus while the underlying work may be authentic, the particular result is a shot designed by Delano himself. The framing also creates a very dense image, in the

sense that each worker is lined up with very minimal personal space, implying that conditions at this needlework shop are tight, yet cold rather than intimate as each worker is fixated on their work. Amidst a background strewn with fabrics, the image comes together to create a direct contrast to the industrial booms taking place in American manufacturing at the time (Field). In other words, there is a direct comparison by which Puerto Rico is made out to be lagging behind the mainland United States.

One of the best indicators of Delano’s shift in mentality comes in the form of this image, seen right. It parallels an experience that he had when first returning to Puerto Rico in 1946, in which he observed a divide between the educational content the children were receiving, and of the nation’s culture (del Pilar Blanco 18). At this point in time, all school instruction was in English, and the English-literature material often revolved around classic tales, inherently populated with stories of fantasy and of wealth. In this way, it was obvious that the forcing of English instruction, and the dominance of the ;iterature by affluence, was effectively equating the two. We see this tension in the image as well, where the American flag is front and center, rather than the Puerto Rican flag. Here, the child’s posing is rigid and the facial expression is one of discontent, indicating a level of disassociation from the ceremony that is the pledge of allegiance. It is also worth noting how the photograph plays with size; the flag is held at an elevation higher than the child’s head, and thus it gives the illusion of being larger than them in the image. In this way, the photo conveys a sense that the principles of American influence are being put above the needs of the child. Other related works show Delano “shifting gears from the systematized practice of domestic documentarism to the unchartered territory (for him) of documenting a wholly different problem:

Puerto Rico’s oxymoronic and uncanny status of foreign domesticity” (del Pilar Blanco 18). In this way, Delano’s later work is motivated not by trying to bring U.S. attention to the financial state of Puerto Rico, but to this tear between the underlying Puerto Rican culture and the transformation U.S. influence pushes it to undergo.

Throughout the remaining photographs, we thus trace a commonality between them that extends to the notion of time as interpreted through culture. Puerto Rico Mío is a project that reflects on this literal time period of the 40s through the 80s as the progression of Puerto Rican culture, at times juxtaposing upon itself, and simultaneously at other times not at all. In the latter case, we can turn to records of the nation's workers.

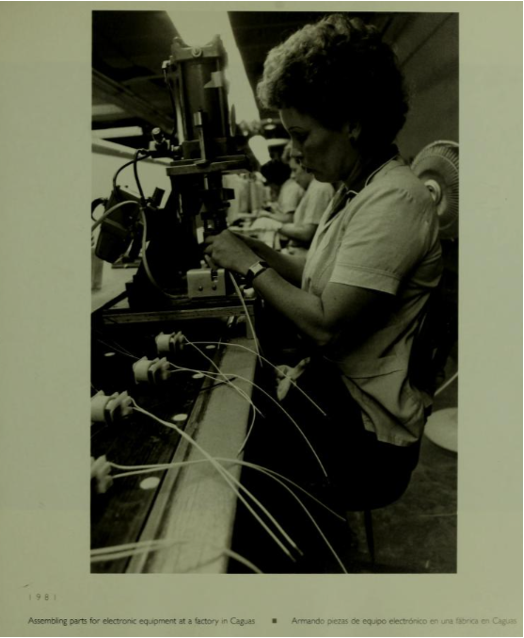

In the book, images are grouped together by subject matter, with images often placed into contrast with one another as in the case of these two images above. In many ways, these images are extremely similar, both featuring a female worker posed similarly, performing a dexterous task. However, the environment and nature of the tasks is immensely different, with the picture on the left featuring an outdoors farming task against the then imminently-modern task of assembling electronics. Despite this contrast, the most telling takeaway from the photos is their similarity, which therein contains no implication that one job is superior to the other. Both workers are intently concentrated, not marked by a difference in emotion but a solidarity in their craft, and a size within the frame that imbues it with a clear demonstration of their competency. Indeed, here there is a reflection on the difference in culture, but not a discouragement one way or the other.

This same notion nonetheless finds itself contradicted by a later cultural comparison made in the book. This time, on the left we see a young girl enthusiastically partaking in stickball, which in and of itself is a reflection of Delano’s shift in presenting the Puerto Rican culture as it is, rather than trying to bring attention to negative qualities. The setting is one of a public school, where genuine entertainment is exhibited simply by making use of rudimentary materials like a plank. The slight bit of blur of blur to the image indicates a sense of movement which only compounds the sense of excitement. The photo to the right presents itself as almost antithetical to that of the left. The style of clothing is extremely different, there is no blur as to capture the relative stillness of the moment, and the expression is serious rather than one of joy. Whereas stickball is a game tied close to the culture of the island, ballet is foreign and takes place within the context of a private setting. Thus, the comparison between the two photos suggests a sort of colonialism that has driven childhood activities in a direction that is in contrast with the “original” culture of the island, and in doing so is implicitly negative. Indeed, these photos by themselves do indeed convey this. However, when seen alongside the previous images, we can see these photos as not merely a binary good/bad, but rather as a demonstration of the push and pull between traditional Puerto Rican culture, and Puerto Rican culture amidst foreign influence. In fact, in this same section there exists a photograph of a young woman partaking in karate classes. Karate finds itself in between these two activities; foreign and poised, yet active and rugged. It is also marked by enjoyment, but also a sense of seriousness. This is all to say, to look at

at any two pictures solely by themselves is to fail to understand both the extent of coverage Delano provides, and to place Puerto Rican culture in an unnecessary binary.

That is, Puerto Rican culture has not evolved from traditional to an American modernist culture, but continually grapples and exists as both at the same time. Both photographs above were taken in 1981, and by placing them next to each other we see that Puerto Rico actively exists as an integration of both the authentically Puerto Rican, and the newly-introduced elements and technologies. While perhaps there is a tension between the public nature with which traditional aspects of culture present themselves, where Americanized elements are more frequently seen in private sectors, the true evolution of Puerto Rican culture over time is not from the nonpresence to sudden presence of new technologies and American influence, but rather from the direct conflict resulting from forcing the English language on the nation, to the gradual assimilation of American elements into Puerto Rican culture. Indeed, throughout the course of the class we have seen ballet removed from its traditional context and performed in a manner reflective of Puerto Rican culture, and we have seen (from my own presentation) a movement of utilizing English not to integrate into American culture, but as a tool for success amidst its presence. Time as experienced by the Puerto Rican culture is both blazingly fast, and rooted in literal cultural roots, and indeed there is no point in assigning it any real direction.

Indeed, throughout this entire time period Puerto Rico has always found itself a reflection of both ends of the culture, and in this sense they are perhaps more turns and bends in a great big loop that is the nation. The image on the left finds itself in extreme contrast with many of the other photos in Delano’s original work, just as the image on the right finds itself in contrast with many of the photos discussed earlier. One might even assume that the photo on the right is the older one, rather than the reality of the situation. At every step in Puerto Rico’s history, it constantly refers back to itself, bringing that culture in every form as it moves forwards. The present Puerto Rico of today is about the same difference in time away from Delano’s original photographs, and in many ways we are left with the same considerations. While success is increasingly tied to a knowledge of American practices and language, the underlying roots are still strongly Puerto Rican. Indeed, as Delano opens his book with a reminder that the lushness and landscape of Puerto Rico persist, we too can do the same.

What ended up pushing my analysis in this direction was my material exploration. As mentioned earlier, we often see natural art taking place before us by thinking too narrowly and trying to produce a singular end result without thinking about the practice. After much stressing and going back and forth over how to go about engaging with the images, by taking a step back and appreciating the presentation of time as evolution in culture, I came to a rather natural conclusion. That is, if the book already sequences the images, and I have resequenced them with respect to pairs amongst different sections, then the next step is to work within these assigned pairs and, rather than contrast them, do exactly what it is that the cohesive product is. Thus, I edited the images in such a way that they show the cohesion, and at times tension, of what it means to move from the time one image captures to the next.

In the following edit for instance, I have isolated the child playing stickball from the image, increased the transparency, and overlaid it with the image of the ballet class. The result is a dualism that shows both progression, unity, and tension all at the same time. Note how the gazes are in different directions, but both with a sense of intensity and both with the same bend in the legs. In this way, we see that, while one is notably happier in expression, the memory of stickball finds itself nonetheless expressed in some ways in the posing of the ballet dancer. The blurring and imposing of one image in the other blurs the notion of a linear time, and tries to illustrate the notion of one Puerto Rican culture, while acknowledging the differences between the two influences.

In the image to the right, I have chosen to make this relationship more explicit. Recall that this is the first pair of images, where the worker sewing tobacco has been pulled off of the original image, and added on top of the image at the electronics factory. With a quick look, nothing looks particularly out of place, and one might readily assume that this is an unedited image, emphasizes the original point made about them; with the sole difference being the literal divide in time, the two workers are united by the ways and the mannerisms in which they work, such that they easily could have worked the same job if not or this literal separation of time. Personally, I was particularly content with this one as it aligned perfectly with what I already knew I wanted to say about the two images, but to see the reality of the result so perfectly encapsulate this dualism was extremely rewarding. We thus see that Puerto Rico has both difference and continuity once again.

As a final exercise, I took the two musical images from the 80s and overlaid them in an even more involved manner, where each image frames the other image in a continual pattern. Each frame is thick enough that the viewer can piece together the individual images, but simultaneously has trouble separating the two. Thus, there is both distinction, and integration, mimicking that same push and pull exhibited throughout the entirety of Delano’s book, and within the culture as a whole. Nonetheless, the traditional culture is both the outer and inner frame, demonstrating the basis on which Puerto Rican culture today exists. Indeed, there will likely always exist this dualism, at least for the foreseeable future, and for this reason it is important to have this cultural definition of time. It is a way of maintaining the underlying culture as it continues to fold and evolve as the world evolves along with it. Indeed, the Puerto Rico of tomorrow is not a different Puerto Rico from today, but rather the product of it and everything that happens in between.

Works Cited

Blanco, María del Pilar. “Picturing ‘our colonial problem.’” Interventions, 18 Sept. 2024, pp. 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801x.2024.2401523.

Delano, Jack. Puerto Rico mío : Four Decades of Change = Cuatro décadas De Cambio. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990.

Field, Alexander J. “The decline of US manufacturing productivity between 1941 and 1948.” The Economic History Review, vol. 76, no. 4, 16 Jan. 2023, pp. 1163–1190, https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13239.

Gonzalez, David. “A Masterwork Spanning 40 Years and One Island.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Oct. 2011, archive.nytimes.com/lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/21/a-masterwork-spanning-40-years-and-one-island/.