Steven Messiah

Subject + Form = Content: How The Frame Changes the Meaning of Documentary and Journalistic Photographs

INTRODUCTION

The meaning of a photograph grows out of the connection between what it shows and how it is made. A subject never speaks on its own. The frame guides attention, shapes context, and tells viewers how to understand the scene in front of them. A wide frame can reveal relationships that exist within a larger environment, while a tight or immersive frame can narrow vision and change the emotional tone of an image. These choices influence what viewers accept as real, especially in documentary and journalistic photography where images often stand in for truth. The frame can clarify, distort, elevate, or conceal. It can open a world or restrict it. Understanding how subject and form work together is essential for seeing how photographs produce meaning and how they shape the stories that come to define a community or a moment in history.

THE CLOTHING DRIVE BY HIRAM MARISTANY

The Clothing Drive by Hiram Maristany (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Hiram Maristany, who “first picked up a camera as a teenager in 1959 at the urging of a social worker named Dan Murrow,” grew into a documentary photographer devoted to portraying the daily life of El Barrio (Harlan). Aside from his photos focusing on the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican social advocacy group, his images captured a community living through poverty and violence, but always with an emphasis on its strength and humanity (Harlan). In 1971, he made Clothing Drive, a photograph rooted in the local activism and mutual support that defined the neighborhood at the time. Reflecting on his work, he later said, “There were a lot of people who cared about each other, who did a lot of positive and beautiful things that never got recognized,” pushing back against the narrow and negative depictions of East Harlem in the media (Harlan). The Clothing Drive image reflects that impulse, showing a community taking care of its own and affirming the dignity that Maristany spent his life documenting.

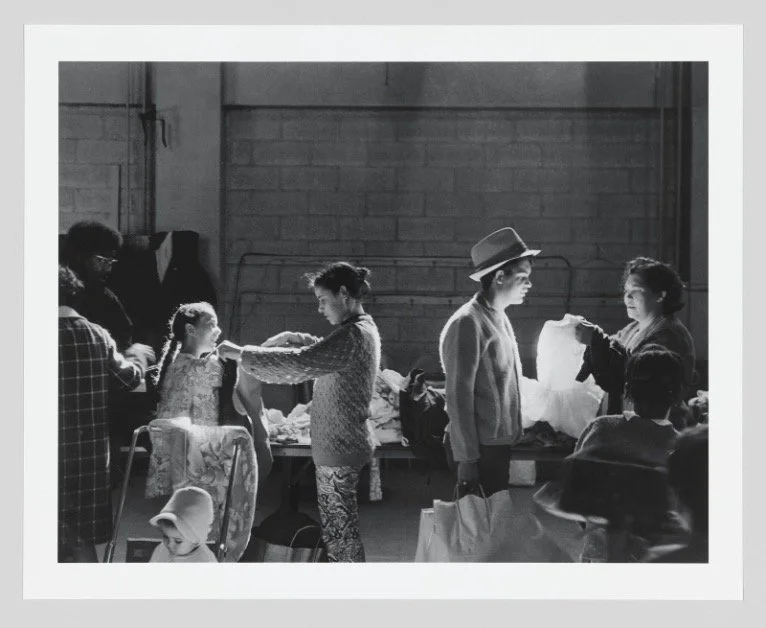

In Clothing Drive, the relationship between subject, form (in this case, the frame) and content becomes the foundation of the photograph’s meaning. The subject is a neighborhood clothing drive, a communal act of care unfolding on an East Harlem street. However, it is the form, especially Maristany’s choice of a wide, encompassing frame, that shapes how that subject conveys its full significance. This expansive angle gathers numerous people, overlapping actions, scattered clothing, and even a visible light source into one continuous scene, allowing the photograph to express the collective character of the moment rather than isolating a single gesture. The wide frame is essential to producing the content Maristany is known for: depicting the daily life of El Barrio in a way that “show[s] metaphors for hope in scenes of everyday life, without glossing over the grit” (Harlan). To represent everyday life authentically, a documentary image must appear ordinary and unfiltered, and the openness of the frame accomplishes precisely that. Nothing feels staged. Instead, the viewer encounters a living environment filled with movement, cooperation, and the natural disorder of a real street. Through this broad vantage, the content of the image becomes a portrait of community with hope expressed through shared labor and mutual support. Visualizing the scene with a cropped or tightened frame makes the importance of Maristany’s choice unmistakable: the collective atmosphere would collapse, and the meaning would shift toward an individualized moment rather than a communal one. The content that defines Clothing Drive exists because the wide frame allows the full story of the neighborhood to emerge.

This wide-angled form is precisely what allows Clothing Drive to communicate its content as a story of collective care, but the importance of that formal choice becomes even clearer when the image is reframed. The original photograph shows a bustling community scene where families and individuals sort through donated clothes, and the full frame includes overhead windows that cast an ordinary, natural light across the room. The scene feels communal and grounded, a straightforward document of the everyday work of survival. When I reframed the image, however, I cropped tightly onto the interaction between the woman holding up the shirt and the man facing her, removing the surrounding room, the crowd, and the light source.

Cropped Photo of The Clothing Drive by Hiram Maristany

This decision isolates only the figures and the garment between them, elevating what appears to be the central act of the photograph—the presentation of the shirt. In the uncropped version, the shirt functions as just one object among many within the broader rhythm of collective labor, illuminated evenly by daylight that belongs to the whole space. But in the cropped version, the shirt begins to glow; without the windows in view, the light seems to emanate from the garment itself, giving it a near-sacred quality. Subject and form combine to produce a new content: a simple act of offering clothing is transformed into a moment of reverence, where the garment carries emotional or symbolic weight. The cropped frame generates a new relationship between light and object, making the shirt appear to be the literal source of illumination and shifting the meaning from the ordinary to the extraordinary. This transformation reveals how drastically framing alters a photograph’s sense of time and significance. In the wide frame, time flows continuously through an ordinary day; in the crop, time suspends around a single, charged exchange. What was once a communal, everyday scene becomes almost devotional, showing that the meaning and sense of time of a photograph is never fixed but shaped by each framing decision made by photographers, editors, and viewers.

HIRAM MARISTANY’S YOUNG LORDS PHOTOGRAPHS: PUBLIC INSTALLATION BY MIGUEL LUCIANO (2023)

Mapping Resistance: The Young Lords in El Barrio. Public Installation by Miguel Luciano. Photographs by Hiram Marsitany (“Madison Avenue | Young Lords”).

Building on the visual language established by Hiram Maristany’s original documentary photographs, this next image shifts attention to their contemporary re-presentation in a public installation created by Miguel Luciano for his project Mapping Resistance: The Young Lords in El Barrio (“Madison Avenue | Young Lords”). The installation is displayed along a chain-link fence in East Harlem, turning the street itself into an open-air archive. The project honors the Young Lords, “a revolutionary group of young Puerto Rican activists who organized for social justice in their communities during the late 1960s-1970s… committed to the liberation of all oppressed peoples, fighting racism and injustice with an emphasis on issues of health, food, housing and education,” a movement whose New York chapter was founded in East Harlem in 1969 and deeply intertwined with Maristany’s photographic practice (Miguel Luciano). All the images reproduced in this installation originate from Maristany’s body of work, yet the photographs of the installation—including the one shown here—were made by Luciano in 2023, adding a contemporary layer of interpretation. In this sense, the project blends past and present and waters the viewer’s perspective of time: Maristany documented the Young Lords as they acted; Luciano documents how their actions are remembered, displayed, and reinscribed into the urban landscape.

Here, the relationship between subject, form, and content shifts dramatically when compared to a single documentary photograph such as Clothing Drive. The subject is no longer just one image or one moment. Instead, the subject becomes the public installation itself: a curated line of Maristany’s photographs arranged sequentially along a sidewalk, extending across space the way a film strip extends across time. The form (the frame chosen by Luciano) is equally essential. By expanding the frame outward to include multiple photographs, the fencing, the sidewalk, the receding line of images, and the surrounding neighborhood, Luciano transforms the meaning of the original photographs. What once functioned as discrete documentaries, now appear connected, almost cinematic, as if the installation were a horizontal reel of historical memory. The viewer perceives the images not one by one, but as a continuous visual passage, and the frame captures this sense of forward motion and accumulation. The content that emerges is no longer only the documentation of the Young Lords in the 1960s and 1970s; it becomes the documentation of public memory in 2023—how East Harlem continues to engage with its political past in the present.

The wide and extended frame is crucial to this shift. By capturing the installation at an angle where the photographs recede into the distance, Luciano creates a formal structure that resembles a documentary filmstrip unfurling across the fence. The long, continuous line of images produces a temporal effect: each photograph feels like a frame in an unfolding narrative, changing the time-scale from frozen images to a continuous, movie-like documentary. Subject + form = content: because the installation is photographed in a way that highlights sequence, scale, and accumulation, the content becomes a story not just of the Young Lords’ activism but of continuity—how resistance persists across decades. The extended angle is therefore essential for a documentary photograph of a documentary installation: it documents not merely the images themselves but the act of publicly displaying them, the neighborhood’s engagement with them, and the layered histories they activate. A tighter crop would flatten these relationships entirely. By contrast, the wide frame renders visible the installation’s cinematic quality, making the street feel like an open-air theater of memory. The result is a photograph in which the public artwork itself becomes a documentary event, and the expanded frame becomes the condition through which its meaning can fully emerge.

A NATIVE PUERTO RICAN THATCHED HUT STEREOGRAPH BY H. C. WHITE CO (1904)

A NATIVE PUERTO RICAN THATCHED HUT STEREOGRAPH BY H. C. WHITE CO (1904) (“A Native Porto Rican Thatched Hut”, The Library of Congress)

A Stereoscope (D.I.Y. Victorian Virtual Reality | Lemelson)

This final photograph operates within a very different documentary tradition from the works of Maristany and Luciano. Produced by the H. C. White Company in 1904, the stereograph emerges from the moment immediately following the Spanish-American War, when the United States had seized Puerto Rico and begun to construct a public narrative about the island to justify its new colonial rule. In these early years of American occupation, photography played a crucial ideological role. Commercial photography companies circulated images of Puerto Rican people and homes that depicted the island as impoverished, undeveloped, and dependent on U.S. intervention. Stereographs such as A Native Porto Rican Thatched Hut were central to that process. Marketed for leisure, consumed in American living rooms, and experienced through stereoscopes that created the illusion of depth, these images allowed white mainland viewers to enter a constructed version of Puerto Rican life as if stepping into a scene that required “saving.” The immersive quality of the stereograph was not a technical novelty alone but also a political tool.

As in the previous documentary photos, understanding how the photo’s form functions is essential to its content (meaning). Unlike Maristany’s wide frame, the stereograph is designed so that the frame disappears. When the two nearly identical images are viewed through a stereoscope, they merge into a three-dimensional illusion. The viewer’s field of vision fills entirely with the scene, leaving no visible border to remind them that they are looking through a representational structure. This erasure of the frame fundamentally transforms how the photograph creates meaning. By enveloping the viewer, the form suggests that the experience is direct, unmediated reality rather than a curated depiction. Subject and form combine to produce a content shaped by imperial ideology: the image seems to show the “truth” of Puerto Rican life, even though that truth is constructed.

The subject (a thatched dwelling with several people standing outside) is presented as representative of Puerto Rican domestic life. But the way it is framed, or more precisely unframed, gives the photograph its power. In removing the photographic boundary and immersing the viewer, the stereograph prevents the distance that allows for reflection or critique. The dwelling appears not as one type of home among many, nor as a scene selected by a photographer with particular intentions, but as an unquestioned emblem of the island’s condition. This collapse of a frame is precisely what colonial journalism relied on. By placing viewers “inside” a humble rural scene, the stereograph generates an emotional response that aligns with the political narrative of the period. What might otherwise be understood as a constructed and possibly staged moment becomes, through immersive form, a persuasive argument: Puerto Rico is poor, its people are living in “primitive” conditions, and U.S. intervention is therefore necessary.

In contrast to documentary work that depends on a visible and consciously chosen frame to construct meaningful content—such as Maristany’s expansive, multilayered views of El Barrio—the stereograph’s elimination of the frame is what enables it to function as colonial propaganda. The lack of a frame conceals the photographer’s position, the staging of the scene, and the selective logic that defines which aspects of Puerto Rican life are shown and which are omitted. It flattens historical complexity by turning a single dwelling into a symbolic representation of the entire island. The immersive format thus becomes a formal strategy that produces an ideology of Puerto Rico being underdeveloped that supports the political aims of the occupying power.

CONCLUSION

The idea behind Subject+Form=Content shows how every choice within a frame shapes what a photograph becomes and how time is felt inside it. In Maristany’s Clothing Drive, the wide frame allows time to feel open and continuous because it holds many actions at once. It shows a living community in motion and gives the moment a sense of everyday duration. In Luciano’s photograph of the Young Lords installation, the extended frame carries time forward across the line of images and turns memory into a slow passage that moves with the viewer. Here the frame waters time by stretching it across multiple images, allowing the past to grow into the present. In the 1904 stereograph of the thatched hut, the removal of the frame compresses time into a single impression that feels complete even though it was constructed to support a colonial narrative. These differences show how form influences the sense of time and the meaning of each image. The frame directs attention, sets the rhythm of what is seen, and shapes how long the moment seems to last. When subject and form work together, the content that emerges defines how viewers understand the worlds within these photographs. This relationship explains how documentary and journalistic images can reveal truth, reshape it, or distort it depending on how the frame is used.

Works Cited

“A Native Porto Rican Thatched Hut.” The Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/resource/stereo.1s16234.

D.I.Y. Victorian Virtual Reality | Lemelson. invention.si.edu/activities/hands-on-activities/diy-victorian-virtual-reality.

Harlan, Beck. “What Hiram Maristany Saw Looking Through the Lens at El Barrio.” NPR, 4 Aug. 2017, www.npr.org/2017/08/04/541268772/what-hiram-maristany-saw-looking-through-the-lens-at-el-barrio.

“Madison Avenue | Young Lords.” Young Lords, www.mappingresistance.com/copy-of-madison-avenue.

Miguel Luciano. www.miguelluciano.com/young-lords/1.

Smithsonian American Art Museum. “Clothing Drive.” Smithsonian American Art Museum, americanart.si.edu/artwork/clothing-drive-110758.