Helpful Reference: https://www.felixgonzalez-torresfoundation.org/works/c/light-strings

By Bonnie Peng

Historical Context

In Puerto Rico, queerness throughout the twentieth century was not only stigmatized, it was constantly criminalized. Under the colony’s penal codes of 1902 and 1974, “sodomy” and “acts against nature” included same-sex relations as prosecutable offenses. This reflects state-backed repression of same-sex intimacy dating from early in history. Same sex sodomy was seen as a penalization offense up to 10 years. These laws stayed in force until 2003, when Lawrence v. Texas invalidated sodomy statutes nationwide, a ruling that applied to Puerto Rico as a U.S. jurisdiction (“LGBT Rights in Puerto Rico”). During the 1980s and 1990s, this legal framework intensified the effects of society perception which in turn created widespread social constructed prejudice toward homosexuality and a climate in which queer Puerto Ricans often lived with fear, silence, and limited legal protection for the crime of love (Bauermeister et al. 379).

Félix González-Torres was no exception to this fear. In 1979 at Puerto Rico’s height of queer discrimination, Félix stepped into a different light of New York and studied at the Pratt Institute as a fellow. In the 80’s, Félix found Ross Laycock. His partner, muse, and heartbeat. A fellowship to Pratt Institute opened the door to an environment where conceptualism, postminimalism, and political art were not only present but actively debated (Spector 14). In New York, González-Torres encountered the Whitney Independent Study Program, which provided him a space defined by critical theory and political urgency, growing his conceptual grounding that would later shape his art. In gleaming contrast to the state of Puerto Rico, the New Yorkers were far more progressive when it came to experimentation with same sex identities.

By the time Félix González-Torres began shaping his artistic voice in New York when the city was entering the deadliest years of the AIDS crisis. What started in 1981 as a cluster of mysterious illnesses quickly became a public health catastrophe (CDC). By 1982, the syndrome was widely referred to as ‘GRID,’ or ‘gay-related immune deficiency,’ which reinforced media portrayals to see AIDS as a disease caused by gay men. This epidemic hit New York harder than almost anywhere else in the United States, and its effects were inseparable from the cultural world González-Torres inhabited. At that time his partner, Ross Laycock, was diagnosed with AIDS (Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation). In 1991 the CDC reports over 80% of people diagnosed with AIDS died within two years, and Laylock unfortunately did not beat the odds (CDC). This loss marked great grief for Felix. Meanwhile in Puerto Rico, this epidemic was equally devastating as the island recorded some of the highest HIV/AIDS rates among U.S. jurisdictions which have been intensified by poverty and the criminalization of same-sex intimacy until 2003 (Bauermeister et al. 379). Stigma towards queer people continued to find its way as causes for under-resourced healthcare, and moral panic produced conditions in which queer grief remained scrutinized publicly and was forced into private intimate spaces.

Image selection and formal analysis

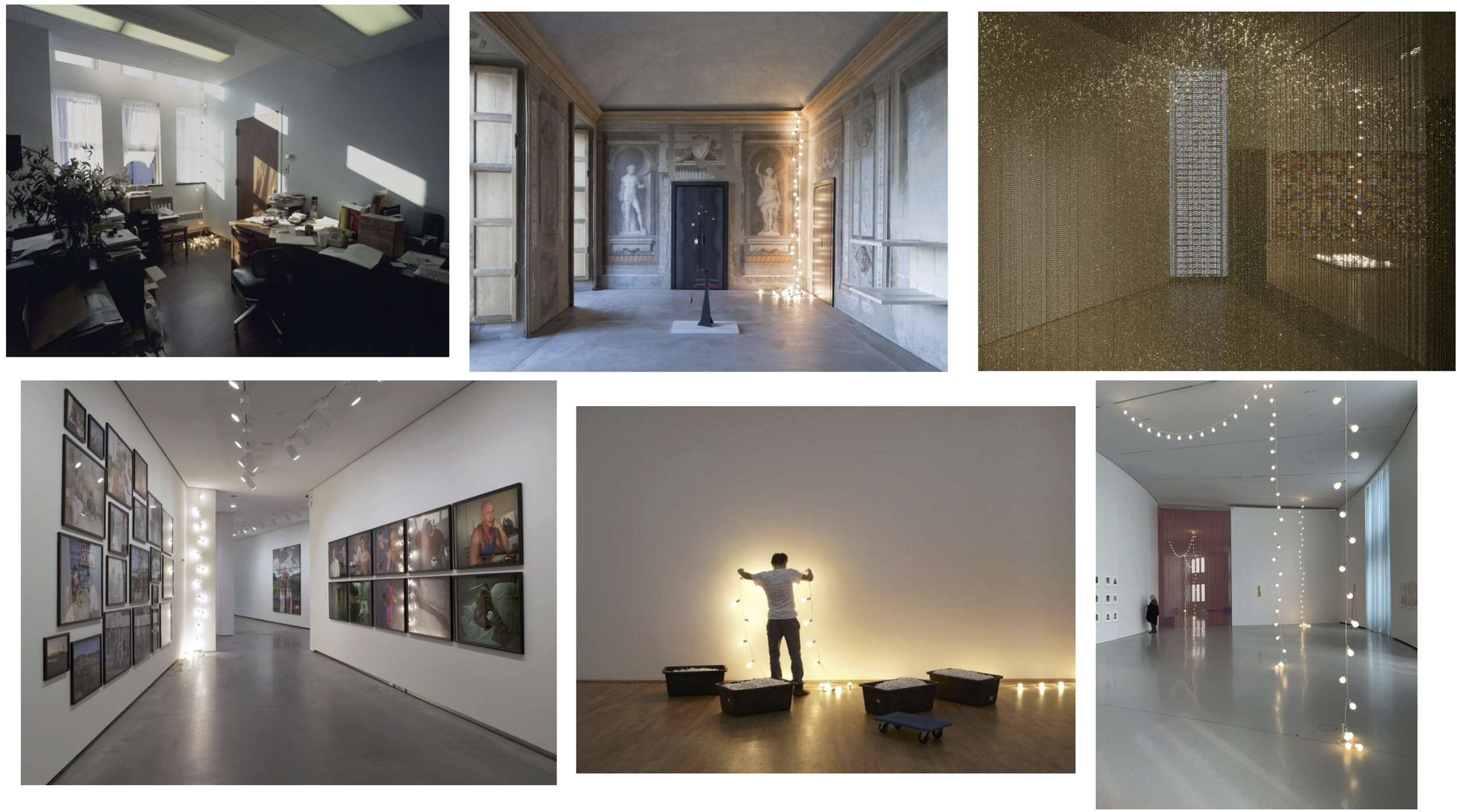

For this project, I chose to delve into the world of light photographed and reimagined by Félix González-Torres provided by his website foundation archive. His installations literally shine light on the loss of his partner during the AIDS crisis and on a society that insisted queer grief remain hidden.

My material experiments focus on visibility: Who is allowed to be seen? Who controls the gaze? How do we make and take images, and what does reframing do to the meaning embedded within them? I began zooming in, cropping, and re-situating fragments of Félix’s works to imagine what each image might be reaching toward whether that be emotionally, politically, historically. Sequencing became another core part of my exploration. How can a set of photographs that struck me individually be arranged into something that breathes, something that holds narrative weight? How do I make their internal logic tangible to my audience? What intrigued me most about Félix is how experimental his material choices are. He uses light, bare bulbs, cords, glows, not just as decoration but as language. So throughout this project, I kept asking myself one central question: Why light? Why choose luminosity as one of his mediums for his time of immense grief, love, and resistance? These questions guided my collages, my reframings, and ultimately the story I attempted to assemble from the fragments he left behind.

I kept returning to the emotional architecture of loss- what grief feels like, what triggers it, how it moves through the body. Naturally, this led me to Kübler-Ross’s model of the five stages of grief. As soon as I revisited those stages, I felt an immediate pull that called to be put to action. Félix’s works already speak in that language. I could see narratives forming inside the light. The five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance all appear in his installations not as literal illustrations, but as emotional states embedded in how the light behaves and constantly shines on some form of truth. The dimness, the glow, the collapse of cords, the insistence on visibility, the quietness of bulbs resting on the floor each resonates with a different facet of mourning. So I began reframing, cropping, zooming, and isolating these works to let those emotional states surface. My collages became a intertwinement- a zine! A sequence where visibility itself shifts with each stage in every disorienting process of grief.

It is also worth noting that all of these works regardless of what folder is titled “Untitled.” That choice immediately caught my attention. Félix refuses to anchor the viewer with a prescribed meaning; instead, he opens the work to interpretation, allowing context, memory, and emotion to shape what the viewer sees. It made me think about how these lights blur time and fiction, because, to me, they aren’t really about lights at all. It just so happened that lights are the object veiling the real subject that is his lover- raising themes of love even. The lights operate as allegories for something deeper Félix wanted to communicate. This also raised questions about artistic intention: how do artists and photographers decide what to reveal and what to withhold? Why choose indirection, subtlety, opacity? Félix’s installations feel intentionally non-literal, almost coded, readable only to those who understand the emotional or historical registers he’s working within- dealing with loss in queer spaces. The non-triviality of his “untitled” choices becomes a kind of quiet invitation to look closer and to sit with ambiguity, to bring your own understanding to the glow as we see elements of light in every photo.

Stage 1: Denial

"Untitled" (America #2), 1992, "Untitled" (Ischia), 1993, "Untitled" (For Stockholm), 1992, "Untitled" (For Stockholm), 1992."Untitled" (America #1), 1992,

Whenever we lose someone or something, we step first into denial, even if we don’t name it that way. Entering this stage is just the beginning. Everything feels eerily normal, as if the world hasn’t moved an inch. The office still looks lived in. The chair still holds the ghost of a body. The light from the sun still shines the same way across the room– a reminder that the world keeps spinning. It’s as if he could walk back in at any moment. Denial convinces us that nothing has changed. Our minds cling to the familiar: his belongings, his laughter, his voice, the texture of his presence. We hold onto whatever we can even if it feels like the world is falling apart. Stringing memories together until they blur, until it feels like we're staring through gold covered tapestry. The images begin to look tinted, distorted as if we’re seeing the world through a frame we refuse to adjust. Maybe that blur isn’t the camera. Maybe it’s us. Maybe it’s the mind’s refusal to see loss as final. In these works, denial appears as a kind of quiet imbalance that lives amongst everyday life. The bulbs that don’t light evenly, cords that don’t quite fall in sync, a room where life remains staged but no longer lived. One side of the conversation is still dialing; the other side is already gone. Denial is not dramatic here. It is subtle, persuasive, and suspended just like these lights. We see the red tapestry in the bottom right, leaking anger somewhere in the distance, waiting. But for now, denial holds the room.

Stage 2: Anger

"Untitled" (For New York), 1992, "Untitled" (A Love Meal) 1992, "Untitled" (North) 1993, "Untitled" (Lovers - Paris) 1993,

Preceding anger was denial, but even in denial there were small flashes of red as warnings. Now, anger arrives in full swing. I arranged these images on top of one another and cropped them intentionally to dial into the details that feel most charged. Anger to me is red: dangerous, volatile, and unavoidable. The central red image almost resembles a wall of blood. It feels violent, opaque and I cannot see through it, which is exactly what anger does. It blocks clarity. Around this red core background, I layered different manifestations of rage. On the bottom left, the tangled bulbs create a sense of disorganization, energy scattered with no place to land. On the top left, the gentle light curtain and the hostile neon text square off like two opposing languages: one tender and private, the other loud and accusatory which is what lots of stereotypes enforce amongst queer communities. Together, they reenact the standoff between queer intimacy and the public narratives that historically sought to shame or contain it. The top-right corner originally belonged to a larger museum installation, but I cropped it down to the chaos which was the mess of wall art, the red-soaked lighting, the dangling bulbs throwing restless shadows. This cropped fragment feels like emotional static that is anger that is present but difficult to articulate. And on the bottom right, that same energy continues. Félix installed these light strings in front of Rodin’s Burghers of Calais, a monument to political betrayal and collective suffering. By placing luminous, fragile bulbs in front of a narrative of state-sanctioned grief, Félix almost stages a confrontation between history and memory between what gets commemorated and what gets erased. Taken together, these images hold a kind of moral anger that's not explosive, but righteous- the right to grieve lovers like everyone else regardless of sexuality.

Stage 3: Bargaining

"Untitled" (America), 1994, "Untitled" (Last Light), 1993

In this stage, bargaining feels like denial wearing a different mask. It’s that quiet, desperate questioning: “Why me?” “Why him?” “Why us?” It’s the stage where we try to negotiate with loss, with memory, with the world that refuses to bend. In the top image, we see Félix’s lights suspended in front of a grand American façade. That collision is intentional. During the 1980s and early 1990s, queer people in the United States faced intense stigma politically, medically, socially, and placing these fragile bulbs against a monumental symbol of federal authority became a kind of plea and confrontation at once. The church image deepens that tension. Catholicism held enormous cultural power in Puerto Rico, shaping norms around sexuality, morality, and belonging. Seeing that vulnerable pile of lights on the floor that are small, dim, almost trembling beneath a towering religious icon carries a sharp emotional pull. It made me think a lot about gaze: the statue gazing down, the shadows falling over the lights, the power dynamic embedded in who is elevated and who is diminished. The lights sit right at the center, like a child trying to be seen by a figure who will never look back. That positioning alone reads like bargaining: a quiet “please,” a question with no response. And finally, the image on the bottom right. A string-light installation hung between the columns of the Smithsonian’s Donald W. Reynolds Center. Those classical columns represent everything that historically kept queer people outside: federal power, nationalism, patriarchal authority, cultural gatekeeping. Against that stone, the lights feel almost tender, almost pleading. They hang there as if asking to be illuminated rather than erased.

Stage 4: Depression

"Untitled" (Toronto) 1992, "Untitled" (For Stockholm), 1992, "Untitled" (America #3), 1992, "Untitled" (Ischia), 1993, Detail of "Untitled" (Arena), 1993, "Untitled" (Arena), 1993, "Untitled" 1992

This stage is one of the clearest in Félix’s work. His installations always seem to reach toward something beneath the visible surface, a deeper register of grief, the kind that settles in only when everything else has fallen away. I intended to reveal a blue hue across this collage because blue feels instinctive for this phase. It carries sadness, loneliness, and the quiet heaviness of depression. That atmosphere sets the tone for the fourth stage I wanted to evoke. The hanging lights feel stripped down, monotone, suspended by a single cord. There is no color to soften them. They look tired, almost drained. The empty table with its vacant chairs sits like a scene after the end of something. It holds absence in a way no figure could. Depression often looks like a room full of objects that used to have meaning, now empty. The third image on the top row, the tangled cords around a phone, stands out to me. It is frustrating, messy, almost claustrophobic. Parts of grief are like that. After bargaining, there is a phase where emotions knot together. You can’t separate sadness from anger or confusion from exhaustion. That tangle is an honest depiction of the aftermath. I also wanted to pay attention to the patterns of the lights in each frame. In the first image on the second row, the background appears at first calm and orderly but if you look harder, there are chaotic coil like shapes. Depression is rarely linear. It comes in waves, out of sync with whatever is happening around you. You can be standing in a quiet room and still feel like everything inside you is collapsing. Félix’s spiral installation in the bottom left captures that perfectly. The lights descend into a circular well, repeating themselves. It mirrors the feeling of looping thoughts, the mental spiral that comes with this stage.

Stage 5: Acceptance

"Untitled" (America), 1994, Untitled" (Arena), 1993,

Finally, out from the shadows, we see a white bird. In the Puerto Rican flag, white symbolizes human rights and individual liberty, and isolating that bird felt necessary for intent. This photograph dates to 1994, the last chapter of Félix González-Torres’s light works, and it reads to me like a turn toward acceptance. After the spirals of denial, anger, bargaining, and depression, this image feels like someone stepping into clarity, not because the grief is gone but because the world has stopped collapsing under its weight, and it feels liberating. The first image in this sequence, the one with the faint text above the lights, includes the line “Many a soldier’s kiss dwells on these bearded lips.” Walt Whitman wrote this in Leaves of Grass, specifically “Song of Myself,” a poem charged with erotic tenderness between men. I surmise Félix chose Whitman because he stands in a queer lineage that existed long before sodomy laws, before medical stigma, before the AIDS crisis tried to erase queer intimacy altogether.

In any present day, the show-and-tell of photography continues to redefine itself across countless spaces. Artists like Félix, who refuses to title his works, open the door for interpretation to move freely. Nothing is fixed; meaning is always in motion. And everything I’ve written lives outside the frame of his installations and inside the lived realities of Puerto Ricans who have carried these emotions long before they had language for them. His lights become a way of holding that history through queer grief, queer joy, queer resistance without speaking it outright. In the end, what Félix gives us is not an answer but an opening to see, to feel, and to imagine how light can survive even the darkest parts of our time, and continue to illuminate the events of many lives of Puerto Ricans throughout time.

Bauermeister, José A., et al. “Sexual Prejudice among Puerto Rican Young Adults.” Journal of Homosexuality, vol. 53, no. 4, Sept. 2007, pp. 135–161, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4154190/, https://doi.org/10.1080/00918360802103399.

“E-Flux.” Artandeducation.net, 2025, www.artandeducation.net/schoolwatch/135355/the-whitney-independent-study-program. Accessed 9 Dec. 2025.

“First Report of AIDS.” Www.cdc.gov, 1 June 2001, www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5021a1.htm.

Gonzalez, Felix . “Works - Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation.” Www.felixgonzalez-Torresfoundation.org, www.felixgonzalez-torresfoundation.org/works/c/light-strings.

Rodríguez-Sánchez, Mario H, et al. “Accidentes En El Lugar de Trabajo Entre Personal de Enfermería Y Su Relación Con El Clima de Salud Y Seguridad Ocupacional.” Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal, vol. 22, no. 4, 2025, prhsj.rcm.upr.edu/index.php/prhsj/article/view/671. Accessed 9 Dec. 2025.

---. “Accidentes En El Lugar de Trabajo Entre Personal de Enfermería Y Su Relación Con El Clima de Salud Y Seguridad Ocupacional.” Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal, vol. 22, no. 4, 2025, prhsj.rcm.upr.edu/index.php/prhsj/article/view/671. Accessed 9 Dec. 2025.

“Sodomy Laws.” Glapn.org, 2025, www.glapn.org/sodomylaws/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2025.

Spector, Nancy . “Felix Gonzalez-Torres | the Guggenheim Museums and Foundation.” The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation, 2025, www.guggenheim.org/publication/felix-gonzalez-torres.

Tomasic, Marisa M. “Five Stages of Grief - Understanding the Kubler-Ross Model.” Health Central, 7 June 2022, www.healthcentral.com/condition/depression/stages-of-grief.

Wikipedia Contributors. “LGBTQ Rights in Puerto Rico.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 6 Dec. 2025.