El Coqui and the Diaspora

by: Patricia Palanik

The coquí, (Eleutherodactylus coquí), is a wider name for a variety of species of frogs native to Puerto Rico. The name coqui comes from the frogs’ defining characteristic: the sound they make (coh-KEE). Coquís are native to the El Yunque tropical rainforest, and they have been present on Earth for 29 million years. These frogs are extremely tiny, they are around 1.3 inches long, yet some are even smaller than a human pinky finger. The coqui population thrives in Puerto Rico; about 20,000 coquis per hectare of land inhabit the island. Notably, they are also one of the loudest amphibians in the world. Their call can be as loud as 100 decibels, which can be compared to the volume of a lawnmower. This project is centered around the coqui, its correlation to Puerto Rico and how it connects to the Puerto Rican Diaspora. The common threads between my chosen photographs are the presence of the coqui itself, its prevalence in Puerto Rican culture, and the threats it faces as a result of human behavior.

Image 1

Photo credits: Perez, Ana

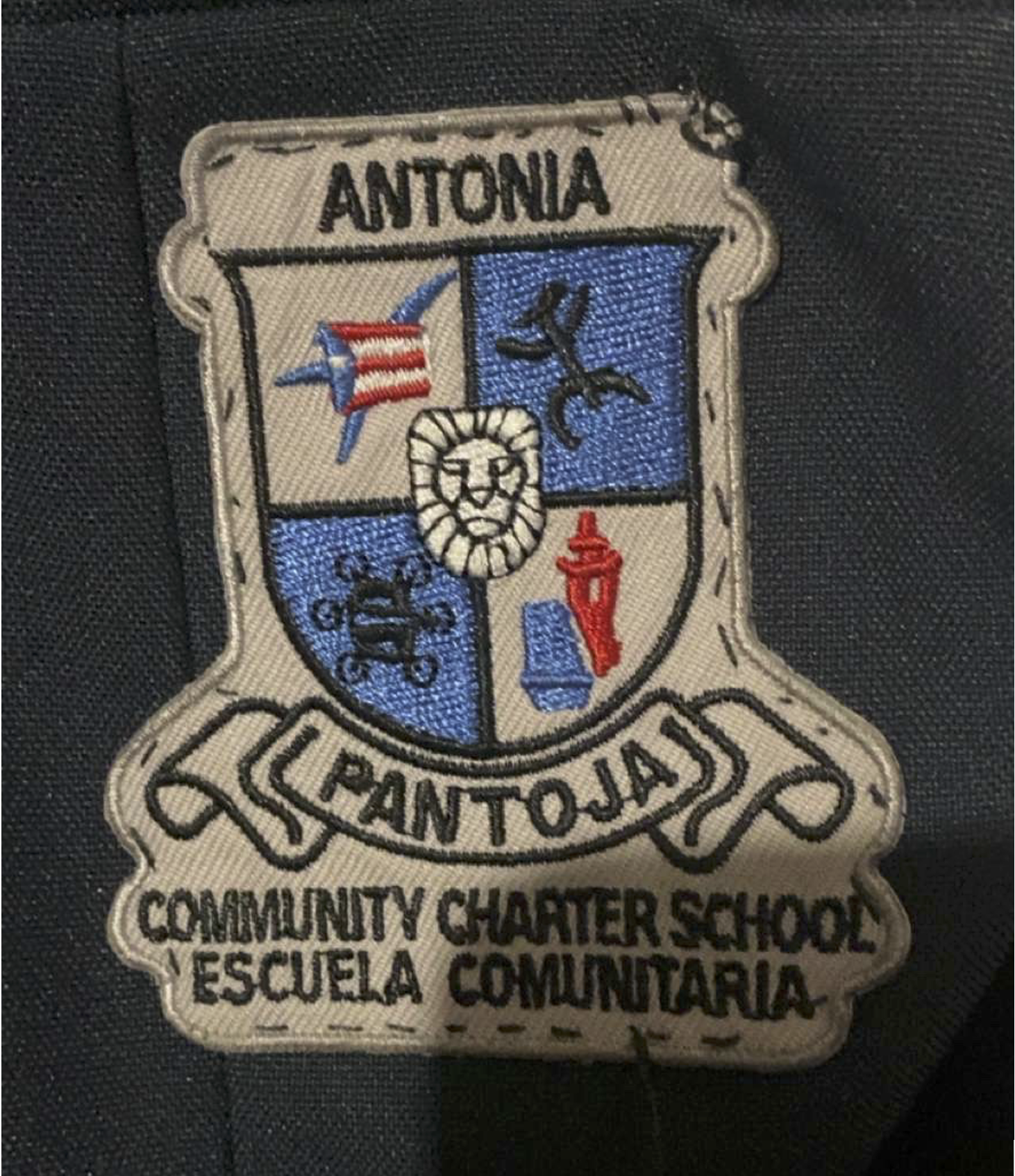

These creatures may just be “another animal” to outsiders, but to Puerto Ricans, they are an integral part of the Puerto Rican culture and identity. The article “A Cultural Symbol of Puerto Rico” by Besanya Ayala explains that these frogs are actually the national symbol of PR, and for natives, their calls are “music to [their] ears as it reminds [them] of home” (Ayala). There is even a well-known saying in PR that correlates to the coqui, proving its importance to the island: “soy de aquí, como el coquí” which translates to “I’m from here, like the coqui” (Ayala). The photo labeled Image 1 above, is a picture of a patch from my best friend, Ana Perez’s, elementary school uniform. Ana went to Antonia Pantoja Charter School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This school’s population consists mostly of Latino students, as the school’s goal is to educate about Hispanic culture and ensure every student graduates eight grade being bilingual in both English and Spanish. Ana herself is Puerto Rican; most of her family still live on the island. The patch in the image contains a symbol of a coquí in the top right section, as well as other integral symbols of Puerto Rican culture. This image of the patch is a primary example of the Puerto Rican diaspora. Even in America, Puerto Rican culture continues to blossom, it is upheld, celebrated, and most definitely not forgotten. There are even schools with specific curriculums designed to ensure that the new generations of Puerto Ricans in the American mainland remain educated about their culture to ensure it transcends generations and stays alive beyond the island. Notably, that specific coqui symbol is rooted from petroglyphs dating back to the 13th century found in caves and rocks in Puerto Rico. The coqui has been engraved into time; their presence unwavering and permanent in the island and its culture. The coqui in this context is a moving symbol, one that can transcend borders as well as time and can that help Puerto Rican culture continue to thrive in other areas of the world.

Image 2

Photo credits: Heidi & Hans-Juergen Koch

The coqui itself has its own diaspora. They are native to Puerto Rico, but they also arrived in Hawaii in the 1980s while hiding in plants being transported there. The coqui population ended up exploding in Hawaii, and the coquis were named invasive species. There is a quote in the article, “A Cultural Symbol of Puerto Rico” by Besanya Ayala that stuck out to me. The author quotes: “We sing songs of celebration, they make plans of eradication” (Ayala). This quote speaks volumes not only about the treatment of the coquis in Hawaii, but also about the treatment of Puerto Ricans and other Hispanics in the modern-day world, specifically in the mainland of America. We have mentioned in class the current state of our country; how innocent Latinos are being terrorized, treated inhumanely, targeted, etc. This, unfortunately, is an aspect of the Puerto Rican diaspora. Image 2 is a photo of a coqui frog sitting on a human’s finger. I placed this picture under a doormat located at one of the entrances of Whitman, where it stayed for two days. The image became covered in dirt and brown water from the rain that soaked through the mat. It also had some dried-up brown stains on it as well as some mulch that most likely found its way under the mat from somebody stepping on the mat and moving it slightly.

My attempt with this action was to express that quote through a photograph and exposing that photograph to elements. The coqui sings its song in Hawaii, but the Hawaiians are collectively working as a community to eliminate the coquis. They are trying to silence the coquis. The act of having possibly hundreds of people step all over a picture of the coqui was supposed to symbolize the oppression the coquis faced in Hawaii, the footprints humans are leaving behind on their populations. Coquis are innocent creatures that have been created to be a villain in the eyes of Hawaiians. The coquis peacefully live in the environment, but the Hawaiians want to eradicate them. This is a symbolic representation of what is happening to the innocent coquis in Hawaii, and to Latinos in the United States mainland in its current political state. Eradicate means to erase something, to move it away, to destroy it. The coquis in Hawaii, which are not only a sacred symbol of Puerto Rico, but living beings with souls, are being targeted. The crumpled, dirtied, walked-all-over state of the coqui photograph symbolizes the harm on both the coquis and innocent Latinos in the U.S.

Image 3

Photo Credits: Portland Flag Association

Unfortunately, the attempt to eliminate coquis is not only happening in Hawaii, but on the island of Puerto Rico itself. The article, “Puerto Rican Coquí Frogs Are Loud. Islanders Want to Keep It That Way” by Kalhan Rosenblatt reveals that in May of 2025, a tourist visiting Puerto Rico made a post on Reddit reading, “Spray to keep the noisy frogs quiet?” (Rosenblatt). This post revealed that tourists who were visiting the island were very irked by the loud calls of the coquis and were planning on killing these native frogs. Allegedly, some tourists did kill coquis by spraying them with pesticides containing citric acid. Coquis breathe through their skin, so a being sprayed by a pesticide is fatal for them. These innocent coquis were murdered due to outsiders visiting the island and treating the environment and its sacred wildlife with selfishness and disrespect. I draw connections between this and the colonial history of Puerto Rico, where outsiders invaded the island, disrespecting its culture, acting greedily. The way I chose to express my frustration as well as this cruel reality through photography is evident in Image Three. This image is one of a coqui with a Puerto Rican Flag edited onto its back. I recreated the horrific actions of the tourists, and placed half a lemon on the image, leaving it there for two days. Just like the coquis were sprayed and murdered with citric acid, I was recreating the process with the citric acid of a lemon without hurting any living coqui. I also hovered a flame over the image (at home) to symbolize the destruction of the environment and to create a more altered image.

The result of the image was very interesting to look at. There are burn marks covering the star and blue portion of the Puerto Rican flag. There is also discoloration created by the citric acid from the lemon. These blemishes on the image symbolize the damage that tourists have done to these innocent animals, which represent the Puerto Rican culture. In this way, not only were the coquis violated by these tourists’ actions, but so was an integral aspect of the Puerto Rican culture.

Image 4

Photo Credits: Pryor, Maresa , and Danita Delimont

I would also like to discuss the effect that photography itself, specifically photography of coquis can impact their population. Because they are so small, they may be seen as pests to the naked eye. Unfortunately, humans do not react well to pests and usually kill them. However, I believe that photography of coquis can allow humans to get to know the animals on another level. Due to the tiny nature of the frogs, photographs of them are usually zoomed in, just like in Image Four.

This uncovers a new perspective of the frogs that humans can see on a new scale. It is also important to note that coquis are most active at night, and it is nearly impossible to spot them with the naked eye. Photographs of coquis allow humans to be able to actually see the coquis, have a new access to them, and interact with them. Coquis and visibility do not go hand and hand, but through photography they do. Now people can see the small toes of the frog, its beautiful body, and its stunning eyes. Allowing a human to look into the eyes of a creature, even if it is on a photograph creates a connection between the image and the viewer. Eyes are pathways to the soul, so maybe individuals looking at a close-up image of a coqui, staring into its eyes, can help them realize that coquis are too living creatures that deserve to live, deserve to be treated with kindness, and deserve to live in peace in their own habitats. In a course I took last year here at Princeton, a topic of discussion was how a camera can create a physical barrier between a human and the subject, but in the case of the photography of coquis, the camera is creating a bridge between them and people.

After the Reddit post, social media was buzzing with images of coquis, allowing these frogs to be seen on this new level by people all around the globe. It has allowed for advocacy for an animal that cannot advocate for itself. Perhaps it has inspired tourists to admire the frogs instead of abhorring them for their natural behavior that they cannot control.

Image 5

Photo Credits: Cruz, Jesann

I also feel the need to mention that some species of coqui, such as the mountain coqui, Puerto Rican rock frog, the golden coqui, and the coqui llanero, are critically endangered. Photography of these animals, especially images that are circulated on social media may allow for the endangered status of the coqui, originally unknown to many, to be acknowledged around the world. This may lead to more awareness, donations to conservation efforts, etc. The coquis were led to this endangered status because of humans, and now the only individuals who can attempt to save these animals are humans, so raising awareness is pivotal. Image 5 shows a gift shop display in San Juan that has an overwhelming presence of coqui themed products in it. From stuffed animals to plastic figurines, to storybooks, the coqui is depicted in these products in a positive way. Stuffed animals symbolize gentleness, love, admiration, connection, which are all qualities that humans should view coquis with. The storybooks about the coquis also present these animals in positive ways, specifically targeted towards kids. These storybooks contain drawings, paintings, and possibly photographs of coquis in them, that are shared with younger generations. These pieces of media can introduce love, care and respect for the coqui to children; views that could remain with them for life. Even Bad Bunny’s Spotify Wrapped video featured a coqui, and his content reaches all ends of the globe. In this way, photography as well as these other forms of media are pivotal in inspiring new generations to care for animals, treat them with compassion, and create a loving connection with them, that can hopefully lead to future advocates for animals, or simply humans who respect the other life forms around them.

Finally, the idea of the endangered status and extinction of the coqui, which has been around for 29 million years is so upsetting and tragic to me. Extinction is in a sense, the end of a time period. It is ridiculous that coquis have thrived in this world for so long, undisturbed, until humans and their reckless actions came around. We, as humans, with our selfish behavior that has been detrimental to the environment and coquis, are slowly inching closer to an end in time- a world without coquis. The coqui would officially be silenced. A species that has stood against the test of time for so long, would suddenly disappear. Human timelines and actions can show that time, specifically the present, can very quickly become the past.

BONUS IMAGE:

Photo Credits: Patricia Palanik

This image depicts Steven wearing a shirt he bought in Puerto Rico with a coqui on it. It is so fitting that the shirt has a hole in the exact spot of the coqui. This too symbolizes the way humans are slowly but surely erasing the coqui. Thread by thread, coqui by coqui, our time with this species is being erased. One day, there may be a world where the loud call of the coqui becomes an echo.

Works Cited

Ayala, Besanya. “A Cultural Symbol of Puerto Rico, Meet the Coquí.” Medium, 25 Jan. 2023, medium.com/the-jibara-story/a-cultural-symbol-of-puerto-rico-meet-the-coqu

Image 2- Heidi & Hans-Juergen Koch. Caribbean Tree Frog (Eleutherodactylus Coqui) Young Frog on a Person’s Finger Tip, Native to Puerto Rico, 2 Spring 2005, www.naturepl.com/stock-photo-caribbean-tree-frog-nature-image00240497.html?srsltid=AfmBOopQo8uwhcvOTRWlsz3f2dpNsWvtoHr0dg9zfYG3GkqsCz5zYK90

Image 3- “Happy (Belated) Leap Day!” Portland Flag Association, Mar. 2016, portlandflag.org/2016/03/01/happy-belated-leap-day/

Image 4- Pryor, Maresa, and Danita Delimont. Common Coqui Print: El Verde, Puerto , 9 Apr. 2009, Ricowww.mediastorehouse.com/danita-delimont/common-coqui-eleutherodactylus-coqui-5777619.html

Image 5- Cruz, Jesann. Coquí Merchandise Sold at a Giftshop in Viejo San Juan, Puerto Rico, 11 Jan. 2023, aces.illinois.edu/blog/2023-01-11t191350/ko-kee-fieldwork-puerto-rico-unpacks-cultural-frog-icon-amidst-amphibian-0

Rosenblatt, Kalhan. “Puerto Rican Coquí Frogs Are Loud. Islanders Want to Keep It That Way.” NBC News, 4 June 2025, www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rican-coqui-frogs-online-effort-protection-tourism-rcna210662