Amalia Nevarez

Framing the Puerto Rican Diaspora: Photography, Time, and the Politics of Representation

All photographs by Frank Espada, East Brooklyn, New York from approximately 1963-1982, and included in his book The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Themes in the Survival of a People):

The photos chosen for this project were all taken by Frank Espada in East Brooklyn, New York from approximately 1963-1982, and included in his book The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Themes in the Survival of a People. I chose these five photos in particular not just because of their visual impact, but because when taken out of their original context they can easily be misrepresented. This potential for distortion is exactly why I chose to create a collage out of them. There’s a difference between a collection of photos put together in a book with great care by someone from the community of people being photographed, and a fragmented collection of images on a social media post. Frank Espada took the time to hear the people’s stories from these communities, and did his best to represent them accurately, as made evident by his quote from the preface that to “to explore, document, consider, and analyze the state of the Puerto Ricans in the United States is a once in a lifetime opportunity”... (Espada 6) He also expressed concern that he would leave parts of the Puerto Rican experience out, showcasing again how important it was to him to do the experiences of these communities justice. This is much different than these images being put together online with a caption thrown on without much thought.

The focus of my final is the importance and nuance of visibility and naming, as well as the medium in which photos are presented. It’s an everyday occurrence for most people scrolling on Instagram to see a photo taken completely out of context adorned with a short caption in large, capital letters. Rarely do people take more than 30 seconds to swipe through the post, take in the information, and move on to the next post. Occasionally they may fact check the post, but the unfortunate reality is that most people won’t so long as the post fits the narrative of what they want to see. (This is more likely than not given that our social media pages are curated to what we like and believe in.) It’s for this reason that I created a collage. I wanted to put together a collection of photos that when given the proper context are truly beautiful, but when cropped strategically and given either minimal or a negatively biased context, can come across much differently.

Visibility is often framed as something positive – as a way to bring awareness to important issues or to give a voice to those whose platform isn’t as expansive as another’s. However, context and intention is very important in creating visibility. Frank Espada’s book, for example, is a wonderful example of someone working incredibly hard to accurately represent a people, taking decades to curate the finished product, and reflecting on the message that he was putting into the world. A social media post created by a right-wing influencer using the images that I put into the collage, on the other hand, would create a very different result. The East Brooklyn Puerto Rican community would indeed gain more visibility, but it may not be in as positive a light.

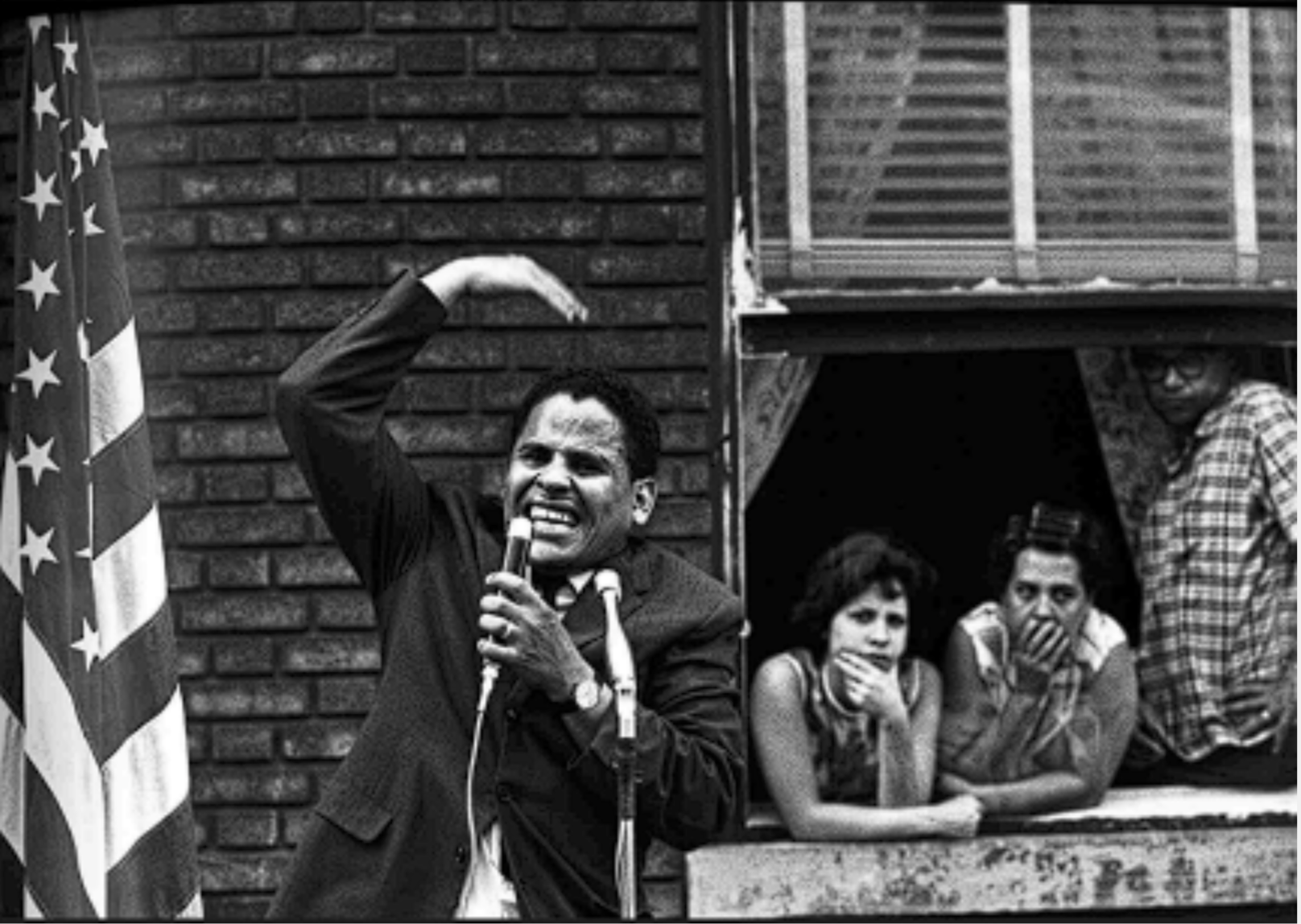

For example, in the photo of the man holding the microphone, the real context is that he was speaking at a Puerto Rican Pentecostal movement event. At the time that the photo was being taken, and even still, there was a lot of racial discrimination in the churches in the area that discouraged Puerto Ricans from attending. For this reason, they built their own churches that emphasized that everyone could get into heaven no matter what their nationality or race was. (Espada 32) To emphasize the potential dangers of visibility, I cropped the American flag out of this photo. Originally, the man (who I’m assuming is a preacher) was standing next to an American flag. It wasn’t torn or displayed in an inappropriate manner, but was standing in the background seemingly as a testament to their dedication to creating an equal religious experience for all Americans. Taking the flag out of the picture allows the caption to become more “creative”. I can easily see the photo being captioned as “Puerto Rican Radicals from New York Try to Change Christianity”.

This example also highlights something fundamental about the role of the camera itself. The camera frames selectively; it includes and excludes, drawing the eye towards some subjects and away from others. Espada’s camera was one of proximity and trust, as he positioned himself close enough to his subjects that the viewer feels included in the scene rather than spying on it from a distance. That same photograph when reframed by someone else can have its meaning changed entirely. What the camera originally showed, connection and resilience, can be undone by later reframing. Form matters: subtracting elements from an image can change its meaning just as drastically as adding new ones can.

The other four images in my collage also reveal important truths about life in East Brooklyn for this Puerto Rican community. In his book, Espada describes the neighborhood as a ghetto marked by “classic slum conditions: housing with no heat, hot water, or basic maintenance and repair, along with an absence of city services...”1 His photographs confirm this description, featuring deteriorating building facades, a child playing in a potentially unsafe environment, and graffiti across many of the brick walls. Yet, Espada’s purpose was not to exploit these conditions or to portray Puerto Rican life as defined solely by struggle. Rather, his lens captures these environments honestly, showing what life was like without reducing the residents to passive victims of their circumstances.

Through careful framing and closer proximity to the subjects, Espada depicts not only hardship but community, strength, and daily rhythm, from laundry hanging outside to dry to people watching a live church service from their window. These photographs don’t ask the viewer to pity the subjects; they ask them to understand the political and economic history that shaped their environment. This approach resists the familiar pattern of “poverty porn”, where images of poor neighborhoods are circulated as a way to shock or shame. Instead, Espada’s photos restore dignity to his subjects by showing their full humanity, embedded within but not defined by the material conditions around them. Including these images in my collage reinforces how precarious photographic meaning becomes when such images are stripped from their historical context. A scene of everyday life could easily be misrepresented as evidence of chaos or the decline of a community depending on who circulates it and why.

Of course, social media wasn’t around at the time of Espada’s publication, but they did have newspapers that could have had a very similar effect. The danger of social media as compared to a paper news article, is that it is very quick and easy to create a post. It doesn’t need to be approved by editors, or provide an idea that is even somewhat widely agreed upon. All one has to do is take a few minutes to put together some photos, and slap a caption of their choice on it. There are actually even fewer limits on fact checking now than there were previously, such as during the pandemic. Posts on Meta platforms used to have a notification on them if they were factually inaccurate, as checked by third party fact checkers. As of January 2025, however, this policy was cancelled. Fact checking is now up to the users themselves because as Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta, said, “third-party moderators were “too politically biased” and it was “time to get back to our roots around free expression”” (McMahon et al.).

The discontinuation of this policy emphasizes how easy it is to spread misinformation on social media, and on Meta platforms in particular. It also demonstrates the lack of control we have over images once they are online. Meta follows the Fair Use Law, which states that copyrighted material can be used for “specific purposes such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching or scholarship.” (“What Is ‘Fair Use’, and How Does It Apply to Copyright Law?”) This covers the way in which most copyrighted images may be used on social media nowadays. This is to say that even if a photo was taken with the best of intentions, it can still be used for malicious purposes online.

Another difference between social media and a physical newspaper or book of photos is that the latter are physically tangible, while the former is not. The physicality of the images changes how long the images are looked at for. When an image is on social media, and you can see that there are 19 other images in the post, it’s unlikely that the average viewer will sit and look at the image, processing its intent and what the photo means to them. With a photo in a newspaper, both in the past and now, one might take a while longer to look at the included images. There are far less images per article, and overall pictures per newspaper, while social media has an essentially infinite number of them. Images in a photo book will likely be looked at even longer, particularly as one probably had some interest in the subject of the photos to even pick the book up.

In this way, time becomes watered by the medium that photography is displayed in. The medium directly influences the amount of time that an image is looked at, and therefore also likely the perceived importance of said images. An image that is looked at for longer may gain a greater sense of importance, simply because the viewer was able to take in the context and impact more, and may commit it to memory more intensely. Additionally, on social media there are a wide variety of images displayed one after the other. It’s hard to take seriously a set of images about the Nuyorican experience when you scroll and the next image you see is an ad for the newest Lululemon leggings. Even if Frank Espada posted the same collection of photos that I turned into my collage, and captioned it with his descriptions from the book, the photos would not be viewed the same way when surrounded by a random selection of posts. For this reason, it’s not just the intention behind the image that matters, or even the caption put on the image; it’s also where and how the image is being viewed.

The tension between medium and meaning raises a larger point: the significance of a photograph cannot be separated from the conditions under which it is made and later re-encountered. Ariella Azoulay’s understanding of photography as an ongoing event rather than as a static point in time makes this especially clear. For her, the photograph is not a sealed record of the past but is a relationship shaped by the photographer’s choices, the subject’s presence, and the viewer's engagement across time (Azoulay). Seen this way, Espada’s images are not just documentation of the Puerto Rican community. They are events shaped by the camera’s framing, by the trust and vulnerability between photographer and subject, and by the political context in which the shutter was pressed. Thinking along these lines also highlights what these photographs can and cannot do: how their form invites certain interpretations while leaving others vulnerable to distortion when recontextualized in fast-moving digital spaces.

Ultimately, Espada’s photographs remind us that images never stand alone. They are shaped and reshaped by the intentions behind the camera, the conditions of their circulation, and the time viewers are willing to spend with them. When presented in Espada’s book, these photographs operate as thoughtful events – what Ariella Azoulay describes as ongoing encounters between photographer, subject, and viewer. When removed from that context and posted on social media, their meaning becomes more at risk of being changed. By making my collage and pointing out my intentions behind the reframing and combining of these pictures, I aimed to make this observation evident. In recognizing the power and instability of photographic representation, we can be reminded of our own role in the photographic event – our responsibility to look at photos carefully and with an awareness of the histories that continue to unfold within each image.

Works Cited

Espada, Frank. The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Themes in the Survival of a People. Frank Espada, 2006.

Liv McMahon, Zoe Kleinman & Courtney Subramanian. “Meta to Replace ‘biased’ Fact-Checkers with Moderation by Users.” BBC News, BBC, 7 Jan. 2025, www.bbc.com/news/articles/cly74mpy8klo.

“What Is ‘Fair Use’, and How Does It Apply to Copyright Law?” Digital Millennium Copyright Act, dmca.harvard.edu/faq/what-%E2%80%9Cfair-use%E2%80%9D-and-how-does-it-apply-copyright-law. Accessed 8 Dec. 2025.

Azoulay, Ariella. Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. Translated by Louise Bethlehem, Verso, 2012.