Valeria Velasquez

Diaspora: Fragmented and United

For this final project, I was inspired by the question we have been asking throughout the entire semester: “Where is Puerto Rico?” I remember hearing this question for the first time and thinking how silly, obviously it is an island (or multiple islands more accurately) located in the Caribbean. However, what I didn’t know was the extent of where this question would take me and the rest of the class to really question where Puerto Rico exists. As we began talking about the diaspora alongside my anthropology course, I realized that a space only has meaning when its inhabitants create and attribute meaning to it. Therefore, a space is only a place when there has been meaning attached. I connected these concepts to our discussions about migration out of Puerto Rico, creating new places throughout the continental US as a Puerto Rican home. I was extremely inspired by Frank Espada’s collection of The Puerto Rican Diaspora, showcasing Puerto Rican communities across different cities inside the United States. Although migration out of Puerto Rico has existed since the colonial period, a sharp spark in migration out of the island and into continental cities became a trend. This happened shortly after World War 2 as the continental US suffered from labor shortages in factories and farmwork. This trend continued until about ⅓ of the Puerto Rican population migrated into the United States, this migration is known as “The Great Migration” (10/9 Diasporic Documentary Practices Slideshow). While the United States was appealing for its job opportunities, the island of Puerto Rico also suffered from push factors that incentivized people to leave. Operation Bootstrap in the 1950s, the period of rapid industrialization for the island, led by Luis Munoz Marin, essentially forced many agricultural workers out of their jobs. Since the island didn’t have enough jobs for these workers, many took the opportunity to migrate inside the US to take on agrarian jobs, eventually staying there for the rest of their lives.

These are the communities that I am most interested in: the Puerto Ricans living inside the United States yet feeling more Puerto Rican than traditionally American, despite being born within the continental states and living most of their lives there. While I have been exposed to the Nuyorican (New York Puerto Rican) community through other readings and images, I was completely unaware that large diasporas existed in places like Chicago, Washington DC, Connecticut, and California. This is why I chose my images to be from these cities where we may not always hear of a strong Puerto Rican presence. All of my selections come from Frank Espada’s work in his collection of the diasporas, and they are all in black and white which was not my intention. Although Espada focuses on the agrarian aspect of migration, I wanted to focus on how else these communities were unified and what drew them to stay together as opposed to returning to their original home. My driving question was then, “what makes this city home?” My images vary in subject matter, come capturing large groups of people and others are more portrait style. While the images standing alone may not tell a complete story, the context and voices of the images is what brings this piece together. Thus, the material exploration that I ended up experimenting with was the sequencing work we did with our Zine projects. Most of my images, with the exception of one, are ambiguous in background, meaning that it is hard to pinpoint the exact geographic location. This was chosen on purpose because the whole point of the project is to show how Puerto Rico lives outside of the boundaries of geography, and how people have internalized this exact feeling to the point where they don’t feel the need or desire to go back to the island. People have made their homes and brought Puerto Rico with them to different parts of the US, and they still live and thrive with their culture.

The sequencing of my images are important, yet in order to explain their purpose and tell their stories, I need to address them one by one. Therefore, I will set the sequence to how I originally wanted it to be experienced and viewed for the first time and then I will go on with my analysis. Sequencing has allowed me to create a narrative that isn’t as clear once looked at for the first time. The first four images are hard to geographically locate, but the last image has a clear indicator of its United States placement. This image being placed at the end is supposed to create confusion and the viewer is supposed to question if all the images are from that location or if they are from different places. Although this is how I wanted the collection to come across. I will also say that since all of the photographs are from Frank Espada’s collection, they are untitled. The following sequence is the collection I have chosen:

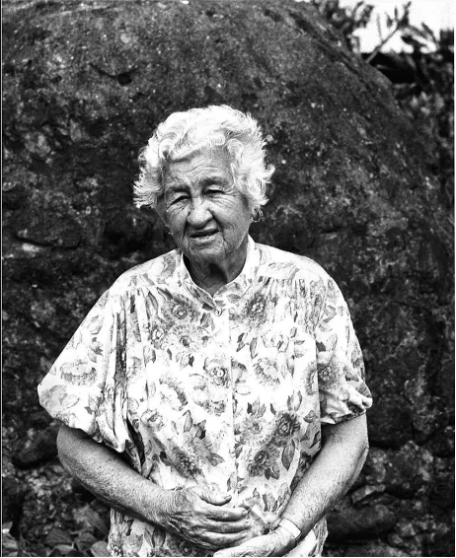

The first image of the collection is located in Hawaii. The title given by Espada reads, “Left Santa Rodriguez Carvalho, in front of a lava oven, Kukuihaele Plantation, Big Island, Hawaii, 1981” (Espada 20). The image, photographed in black and white, has an elderly woman as the subject, smiling while squinting her eyes and her hands placed across the bottom part of her upper body. She is pictured in front of what looks like a large pile of dirt outside but we know it is a lava oven due to the image description. Despite having no color, she is the only part that is bright, our attention immediately looking at her. The placement of her arms are also interesting and draws the viewers attention. I notice her aged skin and due to her standing outside, I wonder if she continues to work in the plantation and I begin to imagine how physically strenuous the work must have been/ may be.

Carvalho’s quote is what struck me about this image: “I was born in this plantation over seventy years ago and have lived here all my life… a lot of memories… this is my home. I wanted to go to Puerto Rico to see where my parents came from, but I never got around to it. But I still feel very Puerto Rican” (Espada 20). Although she was born in Hawaii and has lived there her whole life, Carvalho feels the essence of Puerto Rico in her home and in her identity. I thought it was beautiful to still feel a part of some place she hasn’t even visited or seen. The community and Puerto Rican identity was strong enough in her life where she physically was that it created an imprint on her identity. She is Puerto Rican.

The second image of the collection is another portrait of a young man this time. While once again it is difficult to pinpoint a geographic location, the man takes up most of the frame. His afro fills the majority of the top half of the picture while his face looks serious into the camera. His piercing eyes are a giveaway of their light color, despite being a colorless image. He has headphones hanging around his neck and appears to be wearing a tank top. Although the background of the image is limited and out of focus, done on purpose I am sure to draw attention to the subject in frame, I can tell it was not taken indoors.

The quote associated with this image reads, “What happens in a gang war? A lot of blood is shed. They kill us and we kill them. It’s serious business. I was shot in the side three months ago, they were looking for an Eagle. The bullet is lodged in the spine. I doubt there will ever be a truce; too much bloodshed, too many people dead” (Espada 146). The caption is said by Tommy Jimenez, President of the Latin Eagles, Chicago, 1982. I was reminded a lot about the Young Lords movement we know to be in New York City that we learned about in class. The Young Lords were a radical Black Panther-inspired group of Puerto Ricans fighting for their rights and not afraid of getting physical, and they originated in Chicago. This quote by Jimenez reminds me of the power unity in advocating for equal rights and enacting real and valuable change within the community.

The third image of the collection actually builds on top of the previous work but is not necessarily a portrait. Although there is a girl pictured, rollerskating on the sidewalk, I believe that the main subject of the image is the wall behind her. The wall is actually a door that is used to lock up corner stores in a big city. It has graffiti painted on it with the words “Young Nomadz” and some sort of symbol underneath it.

Upon further research, the words written on the wall are related to the Puerto Rican gang, Savage Nomads, a gang formed in the Bronx made up of people united through struggle, loyalty, and power (Facebook). Although the gang originated in New York, the context of the image is in Hartford, Connecticut. The caption reads, “most people do not understand why there are gangs. It has to do with the fact that we are family, that we look out for each other. Because we are brothers” (Espada 49). The quote can be attributed to Lenny Durio and Angel, members of the Savage Nomads, 1980. Their interpretation of the gang as a family, with connection to the Young Lords in New York and Chicago, really pulls together the act of unity without being physically near. These people were united in identity found, made, and established within their respective communities which was enough of a bond to fight for one another and their rights. Gangs became a way to unify and create communities.

The fourth image of the collection is of a group of people gathered together. Although the subject of the photograph isn’t too explicit, the framing draws our attention to the center of the page, where what looks to be a couple are standing, holding each other. The man’s back is facing the camera and the back of his shirt has the Puerto Rican flag and name. The woman is in front of him, smiling as the sun glares down and holding his arm. The gathering is outside and people around them seem joyous while wearing sunglasses and walking around. It seems to be a celebration.

Although the image does not have a description, caption, or context, I can infer based on the placement in Espada’s collection, that this image was taken at the San Juan Day Festival at Cabrillo Beach, California. San Juan was the patron saint of the island and the day celebrates his life with faith, food, music, and dance (Espada 156). Just by looking at the expression on everyone’s faces that are in the direction of the camera, there is a celebratory tone that comes from looking at the photograph. People are happy and in movement, which the camera captures perfectly. Here, the camera works as a tool for collective memory, joining people together under a united celebration of a traditional saint. The camera captures this memory for generations to come and look back on the unity of the community.

Finally, the last picture shows another group gathering but in a different context. The final image shows a group of people protesting in front of the Washington monument with a bunch of American flags lined up behind them. They are holding up a sign that reads “National Congress for Puerto Rican Rights.” We can assume this is a group of Puerto Ricans fighting for their rights against the Reagan administration (which a sign at the far center back reads) who was actively cutting federal programs that aided the island’s economy and social services (The Counter).

The image seems to be taken from a distance as it captures a large group of people which makes me think about the role of visibility here. The distance acts like a barrier, protecting the identity of people protesting. This is especially important considering the role of the camera inside the island during pro-independent movements. Once again, Puerto Ricans are united under one collective group fighting for a common goal. The community was strong enough inside the states to build this type of unity where people choose to state yet feel connected and affected by cuts to the island.

Overall, as I began analyzing each image I noticed another commonality between them: the outside space. I think it is extremely interesting how an ambiguous background where you can’t exactly tell where an event is located is actually another driving force for unity. People find community on the outside when they are gathered, connected, or even through artwork on the walls. Spaces and communities are not confined to physical boundaries or labels, rather spaces are continuously made and reinforced by the people who choose to create meaning amongst themselves. The United States has proven to be the home of many Puerto Ricans, so where is Puerto Rico? Everywhere.