Noelia A. Quiñones Martinez

Puerto Rican Social Life & Political Revolution Through Internal vs. External Lenses

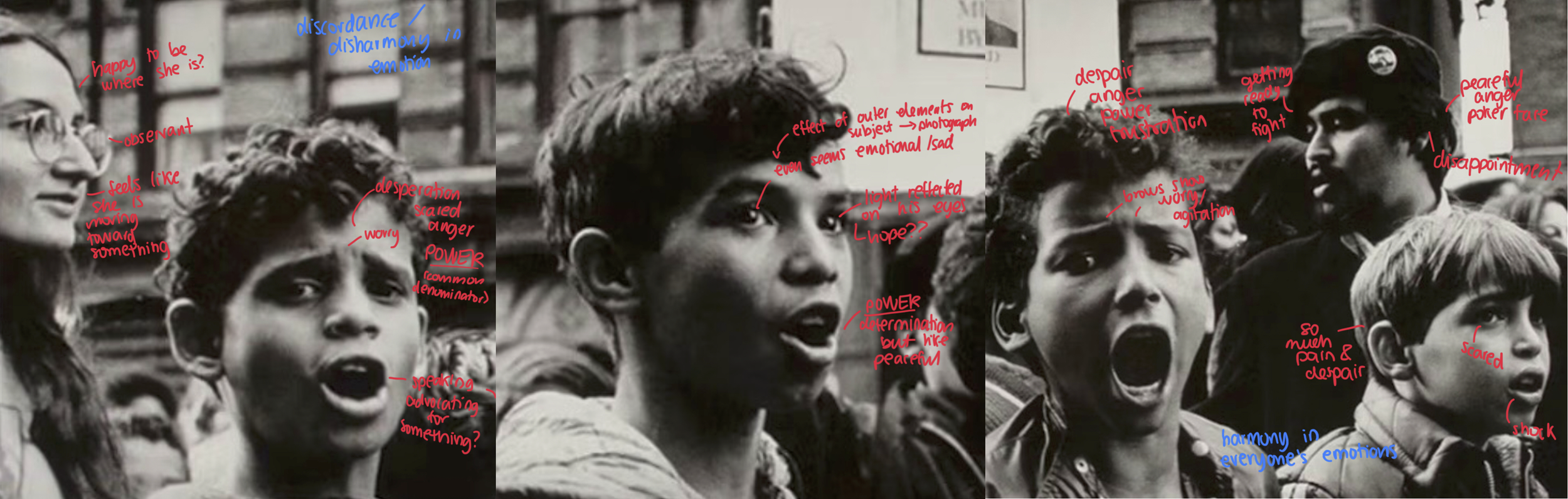

Image 1. Hiram Maristany. Children in the Funeral March of Julio Roldán (1970).

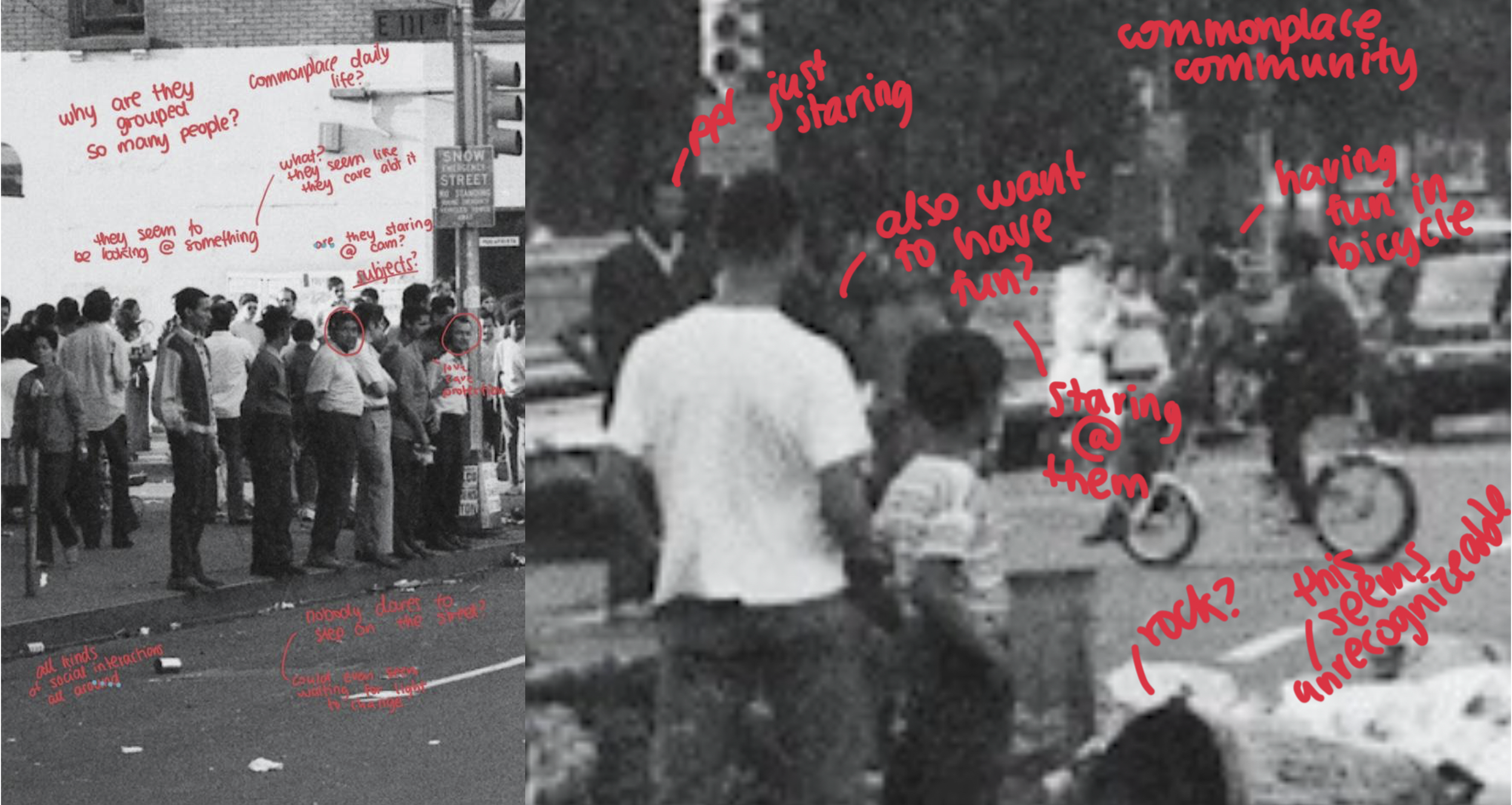

Image 2. Untitled image by Máximo Rafael Colón, “Politics” section in the online image archive website (undated).

A movement, a revolution. Revolutions have always been associated with pain, death and radicalism. The Puerto Rican independence movement (which started flourishing in the 1950’s) has been depicted as a violent and inhumane uprising against the government from members of the radical nationalist party. While violence undeniably occurred, the resilient community that formed in its wake, and the love that sustained it, remain largely overlooked.

Historically, photography has been considered a potent way to archive and record the events within a revolution. It has been considered an objective tool to capture the truth within a story so that others in the future may witness it through them. However, this is not true, and the truth of what goes on beyond an image lies far beyond what we can physically see through it. It greatly depends on what we can’t see: the photographer.

According to Ariella Azoulay (2012), photography is an event shaped by power, visibility, and participation, where the photograph is part of a continuum of events and effects that never end. The position of the photographer, the power dynamic at play within the moment, and the role of the spectator are the greater elements that determine what a photograph is.

Take Image 1 & Image 2 by Hiram Maristany and Máximo Rafael Colón, respectively. Hiram Maristany was a Nuyorican who captured the “everyday life of the East Harlem community, the joys and hardships, the discrimination, self-determination, dignity, and resilience,” remembered as a photographer belonging to a community he loved (NMAAHC, n.d.). Máximo Rafael Colón was also a Nuyorican who documented the struggles, daily life, and vibrant cultural identity from within the community, deeply involved in activism and the fight for Puerto Rican self-determination (Herńandez, 2025). Both photographers were contemporary with the Young Lords movement, which was very much aligned with the Puerto Rican nationalist movement and fight for independence of the American colony.

In the images, we can see the power that flows through them. The spectator can hear the voices of the subjects, screaming for justice and equality during times where there was none.

Julio Roldán was a member of the Young Lords party who was found dead in his jail cell (for reasons thought to be foul play) after having been sentenced when the police apparently saw him set fire to a newspaper (an act considered revolutionary) (The New York Times, 1970). As indicated by the title and the poster in the center of the image, the photograph captures a moment of anger and despair where children and adults alike are marching the Roldán’s name, screaming for justice, fighting for a bigger cause. When we reframe the image and focus on the faces of the subjects, their pain and frustration is evident on the lines of their faces. Though emotions may slightly vary, like we see on the upper left image and slightly on the upper right, we know that the story of the truth behind this image can be told by the faces within it.

Revolutionary movements are often associated with adults who seek to inflict damage to make their voices heard. However, this image’s power comes from the fact that it's focused on children. Revolution is more than an act–it’s a thought, a drive, a common denominator to fight for justice. These may just be children, but they care because they belong to a community that has shown them to do so.

Knowing this image was taken by Hiram Maristany reaffirms the love behind their actions, since the perspective of the photographer is deeply rooted in it. Even so, by truly understanding the history behind the event, we could still feel their desperation.

Likewise, in Rafael Colón’s image, the viewer can also hear the tired, screaming voices of the subjects. By reframing the images and observing each side individually, we observe the harmony present on each side. One, filled with policemen in defensive stances with angry looks, and the other crowded by people attempting to reach something we cannot see, fighting for a cause we don’t quite understand (from within the frame).

When we put them together, we can see how each group sticks with their side, fomenting a sort of division within it. Though the date of the image is unknown, we know it is contemporary with the revolution, and we can infer they’re fighting for the same justice the children marched for above. Similarly, Colón’s image is from the perspective of someone inside the community–someone who understands the frustrations and pain that the people constantly suffer and endure.

The common denominator between both of them: unison. Unity in action, action in unity, and community in unity. A community that goes beyond physical boundaries, defined by shared emotions and collective memories. An unbounded space filled with mutual love, caring, and understanding where people connect through lived experiences and guide their actions by common passions.Though they aren’t necessarily happy, they’re together, because the revolution has joined them into one, and their voices have been amplified by it. One of the most unique aspects of Puerto Rican culture, where most of its values are rooted, is unison.

Puerto Ricans stick together. “The victory of one Puerto Rican over another Puerto Rican is the defeat of the homeland,” like Pedro Albizu Campos said. Puerto Ricans are one, and the people form one. Their power lies in their unity when faced with adversity, and their togetherness no matter the circumstance.

Image 3. Hiram Maristany. Young Lords, The Garbage Offensive (1969).

Image 4. Hiram Maristany. Young Lords, The Garbage Offensive (1969).

Unity in culture also means cohesion in action. The Garbage Offensive, captured in the above images by Hiram Maristany (Image 3 & Image 4) was a nationally recognized protest led by the Young Lords after the city repeatedly neglected to collect trash in their predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhood (Fernández, 2025). By sweeping the streets themselves and dumping uncollected garbage onto them, they publicly exposed the city’s environmental racism and forced political attention to improve sanitation services and acknowledge long-ignored community needs. This event represents the power behind action in unity and how it can make a difference.

Though the pair of the images in itself is a complete reframe, where we are observing the same event from different points of view, possibly at different moments in the relative “time,” we can also gain much information by reframing them. In the reframe from Image 4, we can see a community. Though we see confusion (evidently because of the context in which the picture was taken), we also see joy, family, love, conversation, caring, fun… On the upper left image, we see a woman lying on a man’s shoulder, an act of comfort and trust. In the background scene, we see all kinds of social engagements happening. In the upper right image, we see two people simply riding a bicycle and a man with a child staring at them.

In Image 3, we see a group of people gathered around a car with garbage on the ground. Gathered as a community–gathered with intentionality and care. Both Image 3 and Image 4 are gatherings of people that care about each other, in a neighborhood they care for, because they care for a cause.

Though it is considered an act of “vandalism” and of great revolt, it is rooted from a place of caring, which is another important value in Puerto Rican culture. Puerto Ricans base their actions on their level of caring for what they represent, and they care very strongly, which is based in their unity as a whole. Just like how Maristany cares deeply about his community, hence why he captures images through careful lenses.

Image 5. Untitled by unknown, in the book “El Gobierno Te Odia” by Christopher Gregory Rivera, on page 64 (n.d.)

How do these images change when they are taken from other lenses, though? Through colonial lenses, where the power dynamics are apparent and taken advantage of. Image 5 comes from the book “El Gobierno Te Odia,” which puts together images from the photographic archive of the secret police (which was a hidden police force during the times of “revolution”) in the National Archives of Puerto Rico, paired with text from the surveillance manual given to officers about surveillance techniques. Hence, though this image doesn’t have a specific author or date, we know it was contemporary with the surge of the independence movement and was most likely taken by a member of the Puerto Rican secret police.

Through a reframe material analysis of this image, we can see that in the various frames, we can see a community–a family. The upper left frame includes four people, who seem to be in their 30-40s, engaged in conversation, smiling and seemingly laughing in what seems to be a pleasant interaction shared with enjoyable company. You can see the comfort in their stances and the way they smile (see notes on the people from the frame). The people on the upper right frame seem to be enjoying each others’ company as well, sitting in the back of a car’s trunk, which possibly represents trust in each other. The man in the middle frame seems to have a relaxed stance while he holds a plate. What he probably doesn’t know is that he’s being photographed without his permission. Not only that, but that he’s being photographed as evidence for possible persecution (assuming he is the subject the police were attempting to photograph, which is likely due to his centeredness in the image).

Curiously, the main “subject” seems to be looking straight at the camera. Does he know he was being photographed? Was he simply staring into nothingness? There are some questions we will, quite possibly, never get to answer, and that is how the image breaks “time” and the concept of linearity within it.

Time is a concept created by men in the modern era to flatten multiple temporalities into one linear and standardized timeline (Thu Nguyen, 1992). However, photography breaks this linear time by making the past reappear in the present and altering its temporality. Like how a past moment becomes present for every spectator, how images circulate outside their original “timeline,” and the “event” continues across time and space.

Image 5 is alive, just like every other image we have covered, will cover, and every other photograph that exists, and the event continues in a never ending cycle, always gaining new meaning in different contexts. Even though this image can be considered an invasion of privacy–an act of colonialism with the strong presence of a hierarchy–if we analyze the image considering only what we can observe in it, we can still learn so much about community and the mutual love shared within them.

Image 6. Hiram Maristany. Untitled (1966).

Image 7. Hiram Maristany. Untitled (early 1960’s).

In Puerto Rican culture, family is more than who you share a home with–it’s who you’ve grown up with, who you’ve shared special moments with, and who you have loved and been shown love by. “The family is the first loyalty of the Puerto Rican” (Christoforo-Mitchell, 1991). In these images, both by Hiram Maristany, we can once again observe a community through lenses filled with love. Though there is no way of confirming if this is the same scene from different perspectives, visualizing it as so (as if it were a zine) allows us to witness the caring emotions stemming from the subjects of the images.

In the reframe analysis of Image 6, we can infer this is most likely in a Puerto Rican neighborhood (which is confirmed by knowing this image was taken by Hiram Maristany). The flag, the word “sabroso” in the upper right frame–with these elements, we can see the “orgullo puertorriqueño,” or the “Puerto Rican pride.” Seen in culturally well-known phrases like “yo soy boricua, pa’ que tu lo sepas!” (which translates to “I’m Puerto Rican, just so you know”), cultural pride is an important driver and source of inspiration for many Puerto Ricans.

This pride and love for the island is what moves them towards action, like how it drove the independence movement (which, in itself, breaks the linearity of time as well). Puerto Ricans connect through this mutual love. In the images, we see connection. We see the man connecting with the viandas (which are very important in Puerto Rican cuisine), the happiness in the lines of his face, the women connecting through buying and observing the viandas and the man in the background smiling. They form a community with each other, and belong to a bigger one they all share in common.

Image 8. Untitled by unknown, in the book “El Gobierno Te Odia” by Christopher Gregory Rivera, on page 70 (1975).

Image 9. Image of an untitled image by unknown, in the book “El Gobierno Te Odia” by Christopher Gregory Rivera, on page 70 (1975).

Nevertheless, even if a community is filled with love, caring, unity, and family, there will always be pain and suffering, especially when they’re fighting for a bigger cause, like how these people were. Image 8 captures a presumed protest at the University of Puerto Rico. Arnaldo Darío Rosado (top left, “staring” at the camera) was a college student at the time, and he believed in the freedom and independence of Puerto Rico. Three years after this picture was taken he, along with his friend Carlos Soto Arriví, “would be entrapped and executed by members of the Intelligence Division”, after which the police would be called heroes, while the students were depicted as terrorists (Gregory Rivera, 2023). Though the government tried to cover it up, later videotaped testimony, released in 1983, revealed that the victims were on their knees, surrendering, when officers shot them (the New York Times, 1983). This event, also known as the “Cerro Maravilla incident,” represented pain and suffering for Puerto Ricans, and, to this day, it is still remembered as one of the biggest tragedies during the times of the independence movement.

If we observe the image, we can see a common denominator between the subjects is their focus, which makes sense in the bigger context, considering they are marching in a protest. We can even see social interaction and conversation happening in the image. However, it is important to consider the author of it–these people were photographed without their permission, and we can see the interplay of power inherently present in it. Arnaldo was unapprovingly photographed, unaware that they had intentions of executing him in the near future. In his eyes, we can see the undeniable concern and fear.

Though this text centers around highlighting the community existent within the independence movement and what we can learn from Puerto Rican culture through it, we mustn't forget the pain and suffering many had to endure. We must honor the sacrifices made by others to make the voices of Puerto Ricans heard, and how their actions influenced the way we live today and inspire how we will move in the future.

Image 10. Image taken by a user in Facebook (see link references) (2025).

Image 11. Photograph of the “Ricky Renuncia” protests, by Joe Raedle in GQ Magazine article (2019).

In 2019, the people of Puerto Rico got together to protest against the governor, Ricardo Roselló, after images of a group chat where he sent messages containing all sorts of terrible and inhumane commentary were leaked to the public. In Image 11, we see the people of Puerto Rico gathered around “el capitolio,” protesting for a better Puerto Rico and demanding he renounce his position. This event has gone down historically as one of the biggest Puerto Rican acts of unity, where their love and care for Puerto Rico drove them to speak up for their island, gathering together as one big family to ensure their voices were heard.

The island carried the echo of those protests long after the crowds dispersed, resurfacing years later on the stage, when Bad Bunny released his 2025 album “DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOTOS.” More than a “reguetón” album, the album dove into aspects of colonialism and Puerto Ricans’ hit fight against it. The marketing and concert were centered around the idea of justice for Puerto Rico, like the message on Image 10, projected on screen at the concert, expresses. The album has made a huge impact around the island, and it has even reached international scales. Just like how documentary photography has been used to record events and drive social change, this album exhibits how images circulate around the world, bringing attention to Puerto Rico’s current state as a colony and its struggles within it. Likewise, it reminds us to take more photographs–more photographs to conserve our history and represent our community.

Venter and Bain (2015) argue that revolution is one point on a long continuum of political conflict, not a completely separate category. Likewise, a photograph is one point along the continuum that is time–both of them neverending. We are all connected through this continuum–our actions, our words, our every-day lives. Puerto Rico’s political conflict forms a continuum where Puerto Ricans form a community–a community filled with love, passion, family, caring, unity, and POWER.

References

Azoulay, A. (2012). Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. Verso.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/11S-JhaniFKWSiKPtmYkk2SaiVvIWceCl/view.

Christoforo-Mitchell, R. (1991). The heritage and culture of Puerto Ricans. Yale–New Haven

Teachers Institute. https://teachersinstitute.yale.edu/curriculum/units/1991/2/91.02.06.x.html.

Fernández, J. (2025). When the Young Lords put garbage on display to demand change.

History. https://www.history.com/articles/young-lords-garbage-offensive.

Gregory Rivera, C. (2023). El Gobierno Te Odia, 64-85.

Hernández, M. T. (2025). Photographic Diary: A Conversation with Máximo

Rafael Colón — The Latinx Project at NYU. The Latinx Project at NYU. https://www.latinxproject.nyu.edu/intervenxions/maximo-rafael-colon.

National Museum of African American History and Culture. (n.d.). Hiram Maristany.

https://nmaahc.si.edu/latinx/hiram-maristany.

New York: Young Lords Take Up Arms for “Defense.” (1970). The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/1970/10/25/archives/new-york-young-lords-take-up-arms-for-defense.html.

Puerto Ricans were kneeling when killed by police, officer says. (1983). The New York Times.

Thu Nguyen, D. (1992). The Spatialization of Metric Time: The conquest of land and labour in

Europe and the United States. SAGE, Time & Society, 1(1), 29-50. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Le5wbJeYYZZeTSH7Bpb-yKjgOjhBBYoM/view.

Venter, J. & Bain, E. (2015). A deconstruction of the term “revolution.” Koers - Bulletin for

Christian Scholarship, 80(4). https://doi.org/10.19108/koers.80.4.2246.

Image References

Gregory Rivera, C. (2023). El Gobierno Te Odia, 64.

Gregory Rivera, C. (2023). El Gobierno Te Odia, 70.

La Resistencia PR. (2025). .

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=754217736968954&set=a.147587664298634.

Maristany, H. (1960’s). Untitled, from collection: Looking at East Harlem.

https://smallaxe.net/sxvisualities/portfolios/48#node_783.

Maristany, H. (1969). Young Lords, The Garbage Offensive. Hiram Maristany | Young Lords,

https://whitney.org/collection/works/65758.

Maristany, H. (1970). Children in the Funeral March of Julio Roldán.

https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/712.

Raedle, J. (2019). Why Daddy Yankee, Lin-Manuel Miranda, and Ricky Martin Are Protesting

the Puerto Rico Governor. GQ Magazine. https://www.gq.com/story/puerto-rico-protests.

Rafael Colón, M. (n.d.). Untitled, from collection: Politics.

https://www.maximorafaelcolon.com/.